Focus Sectors

Mining and Resources

Australian Mining Industry

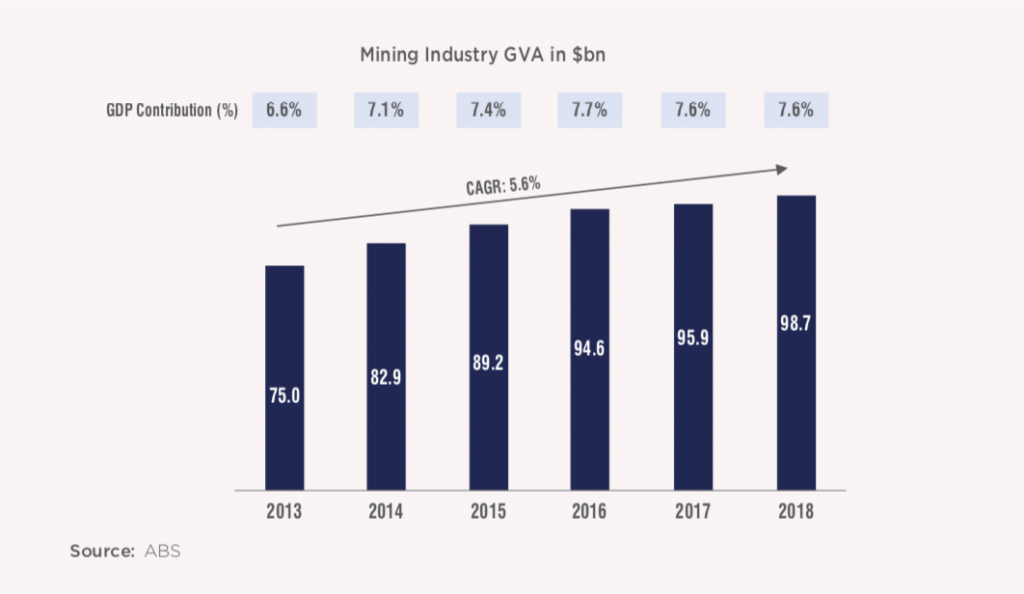

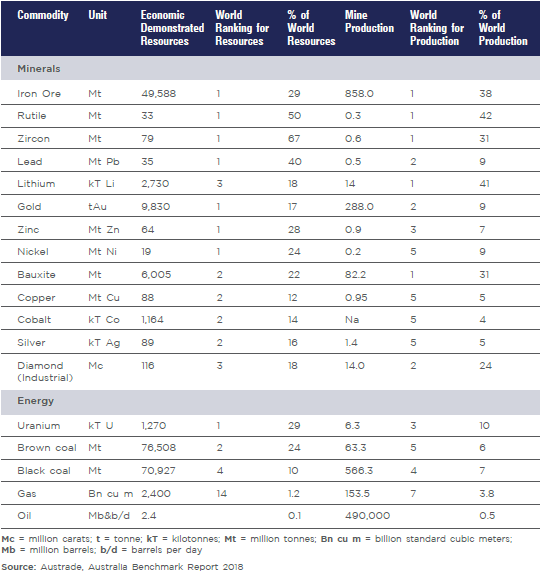

Australia is endowed with an abundance of mineral deposits and mining has been a prime contributor to the Australian economy. Mining contributed ~7.6% to the Australian GDP in FY18.108 Australia is one of the top five producers in the world of 20 key commodities that include gold, bauxite, coal, iron ore, rare earth minerals, mineral sands, zinc, lead, etc. Since FY08, mining has held approximately 50-60% share of Australia’s total exports of goods109 and as of 2019, the mining sector employs around 238,000 people.110

History and current scenario

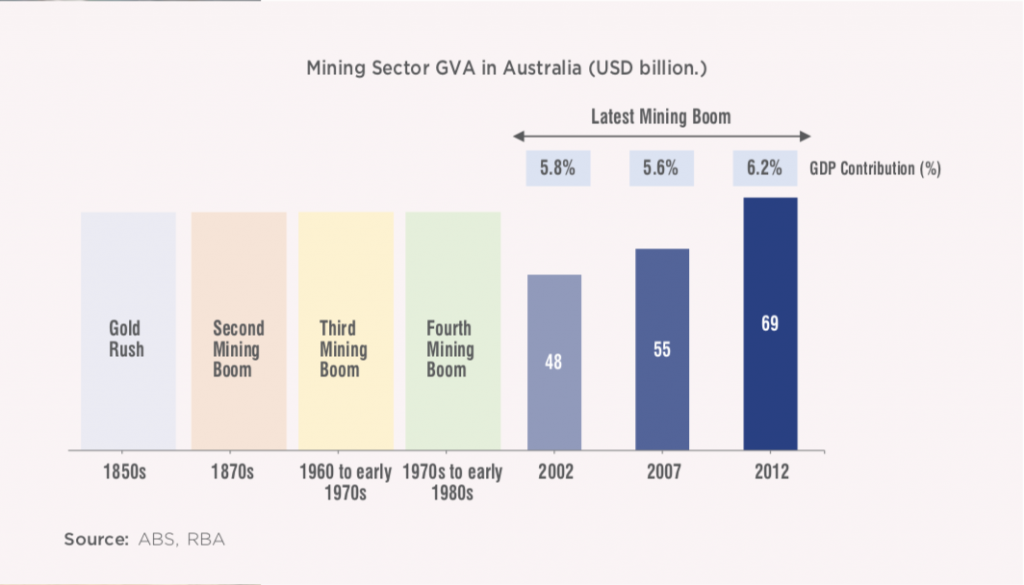

The mining industry in Australia has a history of more than 200 years, during which the sector has experienced multiple periods of heightened economic prosperity, which have shaped the Australian economy. The first mining episode that occurred in Australia was in the 1790s, when coal was mined in the South-eastern part of Australia, near Newcastle in New South Wales. Lead was the first metal to be mined in Australia in 1841, in Adelaide, soon after which copper mining began in Australia. During the 1850s, Australia experienced its first mining boom called the ‘Gold Rush’ with the discovery of gold in the state of Victoria. Gold mining attracted many immigrants and Australia produced a notable portion of the world’s gold in the 1850s, leading to considerable economic progress of the country111. The second mining boom occurred in the late 19th century, when mines were established for copper and gold in Queensland and Western Australia; iron in South Australia; silver, lead and zinc in New South Wales. This led to a further increase in the immigration inflow and boosted economic activity in the country. After this period and during the early 20th century, Australia witnessed a decline in mining activity with fewer minerals being unearthed. However, the country experienced another mining boom during 1960s and early 1970s, when the Pilbara iron ore region was developed in Western Australia and new metals such as bauxite (aluminum metal ore), nickel, tungsten and uranium were discovered. The fourth mining boom occurred during the 1970s and early 1980s due to the increase in energy costs especially that of oil, gas and steaming coal. Post these four significant mining periods, the years between 2003-2012 witnessed a surge in mining activity due to the unanticipated rise in prices of commodities like iron ore and coal, which was caused by a surge in demand from China and other Asian countries. MNCs and small companies that had made initial investments in mines in Australia made higher profits, given that the global demand for iron ore, LNG, metallurgical and thermal coal was at an all-time high.

The period of boom ended after 2013, owing to the slowdown in China’s economic growth coupled with a large supply of minerals in the market by big players such as Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton, Fortescue Metals and Vale. While the sector grew at ~12% CAGR from 2008-2013, the growth has slowed down to ~6% over the last five years.112 However, with commodity prices rising again, there is anticipation of growth in investments and interest within this sector.

Mining industry structure

The mining sector in Australia includes mining of coal, copper, gold, iron ore, nickel ore, oil and gas extraction, petroleum, lithium, among other minerals, in addition to mining equipment, technology and services (METS). Australia has the largest reserves of gold, lead, iron ore, uranium and the second largest reserves of bauxite and coal.

State Wise Profile (important mining states)113

The important mining states in Australia are New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia. In 2017, there were over 300 operating mine sites in Australia, of which approximately 33% were situated in Western Australia, 25% in Queensland and 20% in New South Wales.

Two chief commodities mined by volume included coal (90 mines) and iron ore (29 mines).113 The prime minerals mined in each state are as follows:

- Queensland: The state has major deposits of coal (61% EDR), bauxite (53% EDR), lead (61% EDR), zinc (60% EDR) and silver (58% EDR).

- Western Australia: The state holds a large share in the deposits of iron ore (92% EDR), bauxite (44% EDR), gold (43% EDR), nickel (95% of EDR), diamond (98% EDR), Ilmenite (54% of EDR)

- New South Wales: NSW has significant deposits of coal (36% EDR).

- South Australia: Copper is mainly found in South Australia as the state contributes ~65% to the copper EDR.

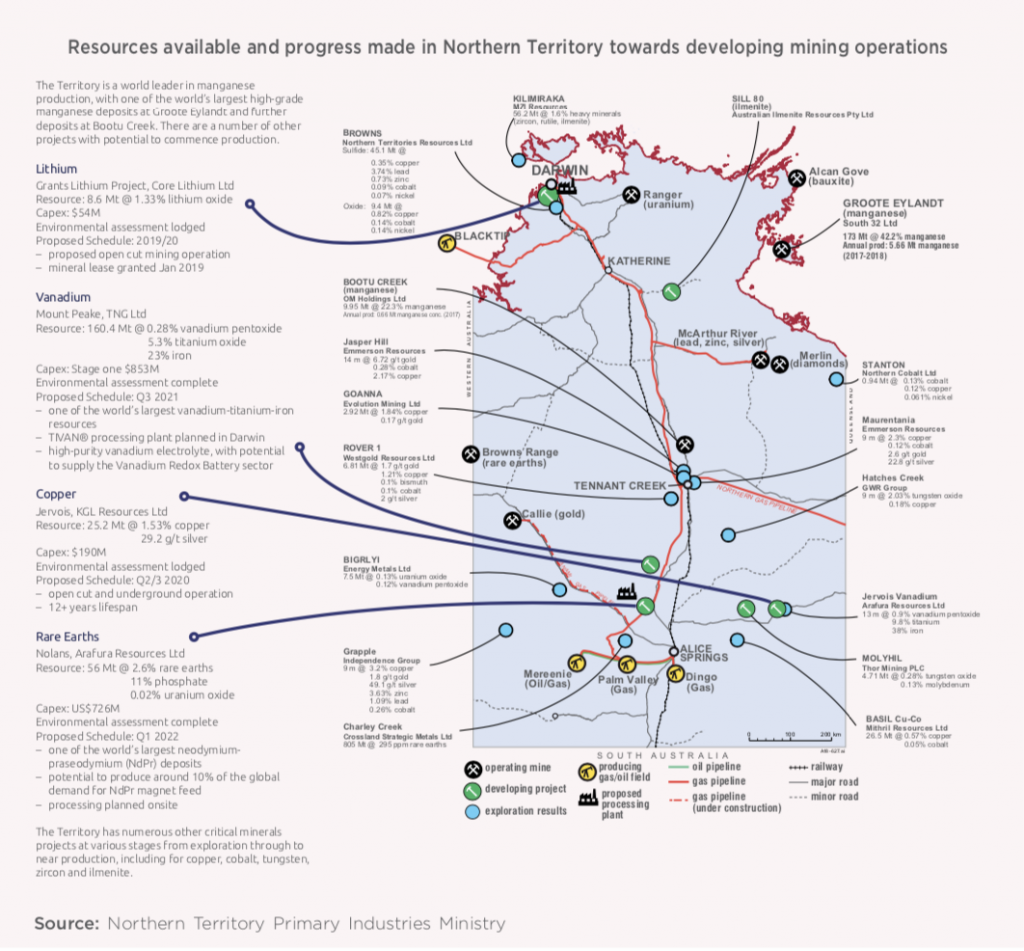

- Northern Territory: Barring the states of Queensland and NSW, which have already established their footprint in the mining sector, the state of Northern Territory (NT) is emerging as a hub for mining and exploration activities owing to the abundant resources found in the state. The State Government of NT is offering competitive tax options for businesses, which are not subject to any land tax in the jurisdiction, as opposed to other Australian states.

Background of selected mining commodities in Australia

Lithium, Cobalt and Nickel

The growth story

Globally, the demand for electric vehicles (EVs) is expected to witness a dramatic increase over the next decade. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated the global electric vehicle fleet size to be over ~5.1 million in 2018. IEA forecasts the number of EVs around the world to exceed 130 million by 2030. China is expected to be the epicenter of this demand; the country is and will continue to be the world’s largest EV market through 2040.114 The key component of EV is its battery, which uses lithium, cobalt and nickel, thereby increasing the demand for these commodities.

Lithium

Australia’s potential

Australia has the third largest reserves of lithium in the world with an Economic Demonstrated Resources (EDR)115 of 2,730 kilo tonnes, as of December 2016. Although Australia accounts for 18% of the world’s resources, behind Chile and China, it was the largest producer of lithium in the world in 2016, with production of 14 kilo tonnes, accounting for 41% of the global lithium production.116 Talison’s Greenbushes project, which is the world’s largest and highest-grade lithium spodumene deposit, contains 34% of Australia’s lithium EDR.117

Currently, a majority of Australia’s spodumene in concentrate form is exported to China for processing, from where it is sent to Japan and Korea for manufacturing battery packs. Although China itself accounts for only 6% of global spodumene production, it accounts for 89% of lithium refining, 75% of electro-chemical processing, 50% of battery cell production and 20% of battery pack assembly.118

In response to the growing demand for battery materials, the production of lithium hydroxide is forecasted to overtake that of lithium carbonate in the next five years. Lithium hydroxide increases the performance and lifespan of the battery compared to lithium carbonate and is produced in a two-step process, in which lithium brines are first processed into lithium carbonate and then into lithium hydroxide. In contrast to this dual process, mining of spodumene from hard rock allows producers to directly process this matter into hydroxide at a lower cost.

The Australian industry believes that the quick and economical processing of Australia’s large spodumene deposit into lithium hydroxide is preferable to the processing of brine into lithium carbonate by all battery manufacturers. Therefore, even while South American deposits of brine have been recognized as the most economical source for lithium carbonate, Australia’s hard-rock spodumene is presented by Australian companies as a superior source for lithium hydroxide. In addition to addressing the growing preference for lithium hydroxide, lower political, business and legal risks in Australia make the country a reliable source of raw materials.

Key companies investing in Australia’s lithium mining

There are several Australian and global companies investing in lithium mining, which include Pilbara Minerals, Galaxy Resources Limited, Mineral Resources Limited and Tianqi.

Pilbara Minerals, an Australian company, is developing Pilangoora Lithium-Tantalum project in Western Australia. Having completed the first stage, the project is expected to increase the spodumene lithium concentrate production to 800,000 tonnes per annum after the completion of the second stage of the project. The company had sent its first offtake shipment to partners in North Asia, thereby reaching a key milestone of commercialization of the product in 2018.

Galaxy Resources is a global company, which operates the Mt Cattlin mine for lithium spodumene production in Western Australia. The ore has a production capacity of 180,000 tonnes per annum.

Mineral Resources Limited operates two mines, namely the Wodgina mine and the Mt Marion Lithium project in Western Australia. In 2018, Mineral Resources formed a JV with Albermale Corporation – the US based specialty chemical company, in which Albermale acquired a 50% stake for USD 1.15 billion119. Albermale has also signed the exclusivity agreement with Mineral Resources and will get access to 750,000 tonnes of lithium spodumene concentrate that is produced by the mine. The Mt Marion Lithium project is also a JV wherein Mineral resources has 43.1% stake, Neo Metals Limited has 13.8% stake and China’s largest lithium producer, Jiangxi Ganfeng Lithium Co. Ltd has 43.1% stake120.

Chinese lithium producer, Tianqi, is constructing a lithium processing plant in Kwinana in Western Australia at an investment of USD 500 million. The plant is expected to be commissioned towards the end of 2019 with a capacity of 48,000 tonnes per annum of high purity, battery- grade lithium hydroxide.121

Opportunity for India

Lithium is the key component of lithium ion batteries, which are used for various applications such as smartphones, tablets, electric cars, buses, motorcycles and airplanes and as battery storage in laptops, stationary items and power tools.

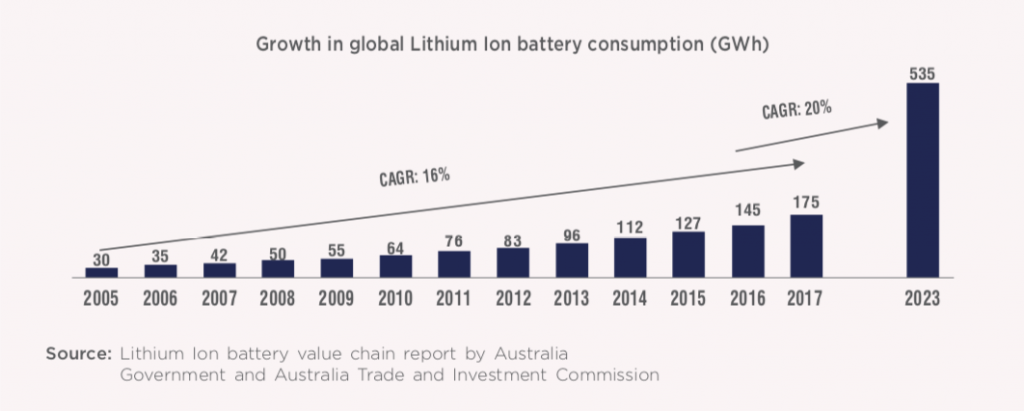

The Indian Government’s initiatives such as the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan 2020, to promote a shift from internal combustion vehicles to EVs, is expected to increase the demand for electric vehicles in India. This initiative is expected to result in growth in demand for lithium ion batteries from ~2.9 GWh in 2018 to ~132 GWh by 2030122, which implies an approximate demand of 10 million tonnes (0.09 kg per kwh of li-ion) of lithium for usage in cells of the batteries. In light of these factors among others such as the Government schemes including FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles) and raising awareness on the use for cleaner fuels, the Indian market for lithium ion batteries is expected to grow at a CAGR of about 29% between 2018 and 2023.123 Organizations such as NITI Aayog are also playing a key role in shaping India’s electrification plans. Several inter- ministerial committees have been set up to look at various demand and supply initiatives, charging infrastructure and last mile connectivity.124 Furthermore, India is also home to about 2.5 million e-rickshaws, which use inferior quality of batteries that eventually need to be replaced.125 Previously, India depended on other countries like China, South Korea and Taiwan for sourcing lithium ion batteries due to the lack of manufacturing setups within the country. However, recently many companies such as Tata Chemicals126, Exide, Exicom, Amaron, Amara Raja Batteries, Mahindra Electric, including companies in the auto and power sectors are considering manufacturing these batteries domestically in India. As the domestic demand for Li-ion battery picks up in India, manufacturing the li-ion cells itself would become feasible in the country.

Increasing investments by different companies in Australia’s lithium mining industry, rising global and Indian demand for lithium and favorable Government policies for promoting EVs in India make a strong case for Indian mining companies to invest in Australia’s lithium exploration and mining companies. Moreover, through a direct or joint investment, India can secure access to Australia’s deposits, while Australia can secure an import partner.

Furthermore, this investment will lead to opportunities for Indian firms, looking to set up manufacturing facilities for batteries in the automotive and power sectors, to collaborate with Australian mining companies for technology and other minerals required in the production of lithium ion batteries. Australian companies should be encouraged to invest in India in the E-Mobility program, processing of lithium and production of lithium ion batteries.

Cobalt

Australia’s Potential

Australia is home to the second highest reserve of (1.2 MT) cobalt after the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Australia accounts for 16.9% of the world’s total reserves of cobalt.127 DRC supplies more than half of the world’s cobalt demand with about 64,000 MT. However, due to the constant political uproar experienced by DRC, Australia has positioned itself as an attractive investment location for setting up cobalt mines.

Key companies investing in Australia’s Cobalt mining

A number of companies such as Aeon Metals, Clean TeQ, Australia Mines Limited, etc. have started exploring different locations within Australia to set up cobalt mines.

Aeon Metals has been conducting exploration as well as infill drilling activities and has completed a preliminary technical and economic study on the potential viability of the Vardy Zone within the global Walford Creek Resource in Queensland. Post the study, the resource estimates were upgraded; cobalt resources identified have been upgraded from 18 million tonnes to 19.8 million tonnes.128

Clean TeQ is a firm that explores mineral resources in New South Wales. In June 2018, the company released a feasibility study stating that its “Sunrise nickel-cobalt-scandium” project has an initial 25- year mine life and ore resources sufficient for 40 years. Further, the production rate for various minerals was estimated to be at 450,871 tonnes of nickel, 84,007 tonnes of cobalt and 250 tonnes of scandium oxide. The firm has laid down a target of commencing operations from mid-2019.129

Australia Mines Ltd released feasibility studies for “Sconi cobalt-nickel-scandium” project in North Queensland in November 2018, revealing that the project would require a capital inflow of ~AUD 1,350 million (USD 905 million). The average annual production of the project is estimated to be 8,496 tonnes of cobalt sulphate; 53,301 tonnes of nickel sulphate; and 89 tonnes of scandium oxide along with an initial mine life of 18 years.130

Opportunity for India

In the first nine months of 2017, India imported cobalt worth USD 3.2 million from Congo, making India the second largest importer after China, which imported USD 1.2 billion worth of cobalt in the same period.

Cobalt has been identified as the main component of the lithium ion battery required for EVs in addition to lithium. This is expected to develop interest in investments towards cobalt mining along with lithium. As a result, Indian companies as well as the Government can look at engaging into partnerships with Australian mining companies. Public companies like Nalco, HCL, MECL and others, as well as private companies that are assessing opportunities in this sector, can look at Australia as a potential option for sourcing these minerals on a long-term basis.

Nickel

Global Scenario

Nickel has been historically used primarily to produce stainless steel. With the growing EV demand, the demand for nickel is expected to rise. EVs could also use batteries with nickel- manganese-cobalt (NMC), which has the potential to further fuel the demand for nickel. Currently, the global nickel demand stands at USD 20 billion. This figure is expected to be supported by the growth in EV penetration. Many countries have made a commitment to banning modes of transportation that causes emissions. The UK and France have committed towards banning fossil fuel car sales by 2040, India has announced plans that every car sold by 2030 would be an EV vehicle and China, the largest automobile market in the world, has planned to ban gas vehicles, to achieve pollution targets. Global economies in this sector are transitioning to adopting environmentally conscious policies.

Australia’s potential

Australia ranks at the top worldwide in terms of nickel resources, with 24% of the world’s known economic nickel resources situated in the country, followed by Brazil at 13% and Russia at 10%. The EDR of Nickel in Australia stood at 18.5 MT, in 2016, with Western Australia as the leading holder of the resource at 96% and Queensland holding the remaining reserves. The country is also the 5th largest producer of nickel in the world.

Key companies Investing in Australia’s Nickel Mining

Companies such as BHP, Independence Group and Western Areas are increasingly investing in nickel mining.

BHP is continuously working towards nickel exploration and mine development and has plans to set up a battery grade nickel sulphate plant in Western Australia. The Venus deposit in Western Australia houses more than 200,000 tonnes of nickel reserves. The firm is targeting commencement of operations at the plant from April 2019 with a capacity of 100,000 tonnes of nickel sulphate. The firm is also looking at doubling the capacity with a potential second stage expansion in the works.131

Independence Group owns the Nova nickel-cobalt copper sulphide underground mines in the Fraser Range located in Western Australia. The mine site was discovered in 2012 while commercial operations commenced in July 2017. In FY18, the mine produced 22,258t of nickel and 9,545t of copper. The firm is exploring further to target resource extensions beyond the current identified area.132

Western Areas owns the Forrestania mining project and is home to two high grade nickel mines i.e. Flying Fox and Spotted Quoll. The project is expected to produce 20,500 - 22,000 tonnes of nickel concentrate in FY19. Western Areas commenced operations of the two mines in 2006 and 2007 respectively.133

Opportunity for India

India does not host any primary resources of nickel and is, therefore, largely dependent on imports. However, nickel sulphate crystals, a by-product of copper production, is found in India. The annual pure nickel demand in India was estimated to be 45,000 MT. In FY17, imports of nickel ore and concentrates stood at 1,062 tonnes, primarily from Guinea and Australia. Australia accounted for about 25% of the import of nickel and concentrates in FY17. India will continue to depend on imports of nickel till the technology for utilizing nickel from Odisha can be commercially established.134 Indian companies can form a JV or evaluate greenfield opportunities for nickel mining in Australia to meet India’s growing nickel consumption.

Critical Minerals Required in India vs their supply in Australia

India’s Critical Minerals Strategy has identified 49 minerals that will be vital for India’s economic growth. Australia has reserves of 21 of these critical minerals that could prove complementary to India’s requirements.

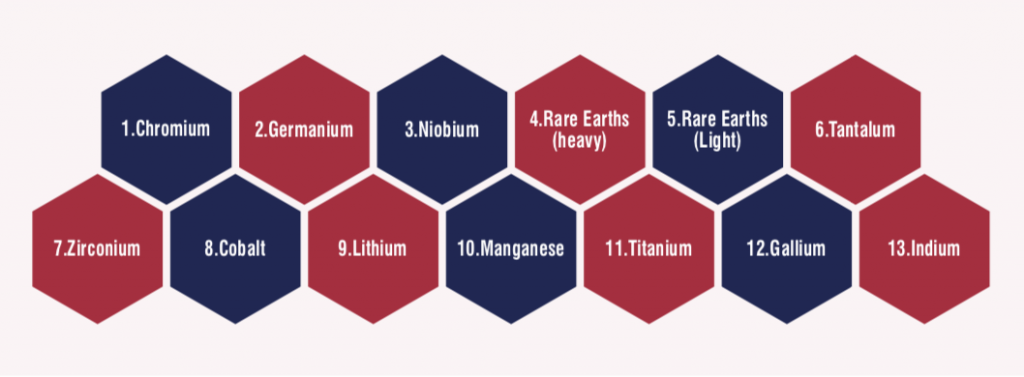

Of the 21 critical minerals on India’s list, Australia has identified the following 13 minerals as ‘High Potential Geological Opportunities’:

Of these thirteen minerals, ten are currently imported in India, with the exception of zirconium, manganese and titanium, where there is some domestic supply available in limited proportions.

Apart from these, Australia also has reserves of eight other critical minerals, which include the following:

Of these, India is 100% import dependent for all except graphite and magnesium.

Many rare-earth minerals, including neodymium and dysprosium, are required in the manufacturing processes of electric motors and other end-use products, which are essential for India to secure its manufacturing requirements. In 2016, India imported ~USD 3.4 million worth of rare earths, of which ~USD 3.4 million was imported from China, Hong Kong and South Africa.135 According to the Indian Mines Bureau, India has a total consumption of ~31.9 tonnes of rare earths that is expected to grow in the near future135. In India’s effort to secure a supply of rare earth minerals, Australia can be a key trading partner.

The Australian Government is keen to develop its critical minerals sector and is encouraging international investments in this sector to increase downstream processing activities. Several critical minerals typically co-exist and require separation using extensive chemical processes. Hence, the economics of processing critical minerals is very different than that of bulk commodities. Additionally, the critical mineral markets are highly monopolistic and have complex value chains. The complexity of value chains, high investment overhead for processing and small markets imply that only a handful of companies and countries can participate in any one critical material market.

Australia has initiated separate talks with the US, Japan and Korea over the development of critical minerals projects in an effort to diversify global critical mineral supply chains. Australia has also recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Field of Mining and Processing of Critical and Strategic Minerals with India. These mechanisms of cooperation focus on how best to help projects in access to financing and securing long- term supply deals, cooperation on research and development and efforts to develop resilient global critical mineral supply chains. Australian based mining company, Lynas Corporation Ltd., is the world’s largest rare earths mineral supplier and processor, after China. While China contributes 85% of the global production of high-purity rare earth minerals, Lynas produces the subsequent 15% for the world. Lynas has strategically partnered with the US to build upon its processing segment. Similarly, Australia can collaborate with India in setting up plants to process its rare-earth minerals in India.

Due to India’s high dependency on imports of critical minerals and the need for an effective strategy to source the rare earth minerals, it is important for India to collaborate with Australia in this area.

Australia offers a secure and reliable political environment, adequate resource endowments and processing technologies along with transparent Government frameworks. Furthermore, Australia has always shown an active interest in engaging with India. India’s focus on resource security and Australia’s commitment towards developing the critical minerals sector, should pave the way for a long-standing supply and investment relationship between India and Australia, which will be beneficial to both countries.

Coal

Growth of the sector in Australia

The coal industry in Australia witnessed rapid growth between 1960 and 1986 due to the establishment of the Joint Coal Board and the conciliation labor tribunal. Australia began exporting coking coal, used in steel production, to Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan and benefitted substantially from the growth of these markets. With the expansion of the industry, Australia developed a competitive advantage because of cost competitive operations and improved efficiencies such as the emergence of the open-cut mining technique. Between 1987 and 2003, the entry of Indonesia and China in the coal industry increased global competition. Indonesia gradually became Australia’s principal competitor for the thermal coal market in Asian countries. In 2017, Australia exported 372 million tonnes of coal, with thermal coal accounting for 200 million tonnes.137 As defined in Australia, Black Coal can also be used

to produce electricity.

Australia’s potential

Australia has emerged as a global leader of brown coal resources (second largest in the world) and black coal resources (fourth largest in the world). Brown coal is used for electricity generation (thermal coal) and black coal is used to produce coke (metallurgical or coking coals), which is used in blast furnaces to produce iron or steel.

In 2017, Australia had 10% of black coal and 24% of brown coal of the total global resources, respectively.138 Dependence of the steel sector on imported coking coal will remain constant in the foreseeable future. Australia is presently the single largest source of coking coal imports for India. Coal found in Australia has high demand because of its high energy content and fewer impurities. This coal can be readily used in high efficiency-low emission power plants and steel mills.

Recent investments in Australian coal industry

Rio Tinto’s decision to exit coal mining to focus on iron ore, copper, bauxite and aluminum operations led to a number of deals in the Australian coal sector.

The Greens introduced a Coal Prohibition (Quit Coal) Bill 2019 that mandated the prohibition of mining, burning and the export and import of thermal coal in Australia. The bill specifically listed the phasing out the export of thermal coal by 2030, prohibition of the establishment of a new coal mine or coal-fired power station and the burning of coal after January 2030. The Bill, however, was not passed, and lapsed upon dissolution of Parliament in 2019.

EMR Capital, a private equity firm and Indonesia’s PT Adaro Energy bought the Kestrel Mine in Queensland from Rio Tinto for USD 2.25 billion (AUD 2.9 billion). In 2017, the mine produced 0.84 million tonnes of thermal coal and 4.25 million tonnes of hard coking coal.139

Rio Tinto also sold its coal mine in Hail Creek and Valeria coal development project to Glencore for USD 1.7 billion. The Hail Creek mine had 601 million tonnes of mineral reserves and 142 million tonnes of probable reserves at the end of 2017. It produced 4.1 million tonnes of thermal coal and 5.3 million tonnes of hard coking coal. With this acquisition, Glencore, which is already the world’s biggest exporter of thermal coal, will now have a bigger stake in metallurgical coal.140

In September 2017, Yancoal acquired Rio Tinto’s wholly-owned subsidiary, Coal & Allied Industries, for USD 2.69 billion. In 2015, the mine produced more than 13 million tonnes of thermal coal and semi-soft coking coal.141 As a result of this acquisition, Yancoal Australia Ltd and Yanzhou Coal Mining Limited, which is the controlled entity of the Chinese Government holding 78% stake, along with Glencore will dominate exports of Australian thermal coal.

Mitsubishi sold its 31.4% stake in Clermont coal mine located in Queensland to GS Coal, a 50:50 Glencore-Sumitomo joint venture. Clermont is a large-scale open-cut operation, with an annual production capacity of around 12 million metric tonnes of thermal coal.142 Furthermore, Australia provides a stable legal framework that is amenable to foreign direct investment in coking coal assets.

Key geopolitical developments

As part of the Paris Climate Change Agreement in 2015, several countries pledged to decrease their greenhouse gas emissions and limit the increase in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial levels. Amidst growing pressure from global environment groups and Governments, a number of global banks and financiers, such as Standard Chartered, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas, Barclays, etc. have decided to either entirely stop funding or decrease their exposure in coal investments.

Moreover, Japanese financial institutions, which have been at the top of the list in terms of global financial institutions funding new coal-fired power plant developments, too, have taken significant steps to exit coal. ITOCHU, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Marubeni Corp, Mitsui & Co and Mitsubishi Corp have all announced their intentions to exit the thermal coal sector.

Regulatory challenges in Australia

Australia’s banks are facing increasing pressure from environmental and progressive activist groups to stop funding new coal projects and to honor their public commitments to the Paris Agreement. Despite this backlash, the current Government’s new power generation underwriting program aims to fund generation projects, which include upgrading of coal generators and other greenfield and brownfield projects, which use conventional sources of energy (fossil fuels).

In February 2019, a court in Australia denied permission to develop a new coal mine in Hunter Valley, New South Wales as the mine was expected to generate high greenhouse emissions, causing environmental pollution.

The situation with India’s Adani Group is a classic example of the opposition from environmental activists and the public. Adani Enterprises began acquiring the Carmichael coal mine and railway project in 2010 with efforts directed towards completing environmental and technical studies and gaining approvals.143 Though the Australian Government had initially supported this project, soon after this investment, the Carmichael mine faced heavy opposition and it was conveyed to Adani that the mine was expected to cause severe damage to the Great Barrier Reef in addition to generating massive greenhouse gas emissions. These factors led the Adani group to downsize the investment from the initial planned value of AUD 16.5 billion to AUD 2 billion (USD 11 billion to USD 1.3 billion). The planned production was also reduced from 60 million tonnes/ year to 27.5 million tonnes/ year in the first phase of operations.144 In November 2018, after the main Australian banks refused to fund the project, Adani Enterprises self-financed the scaled down version of the mine with the aim of gradually ramping up production over time to 27.5 million tonnes per annum. The group has finally received all clearances in 2019 and expects to start shipping coal from the mine by FY21145. The example of Adani, Jindal Steel and Power ltd (which has invested in mines in New South Wales) and several other Indian Companies - many of whom have faced delays in environmental and other clearances -has prompted a rethink on strategy in investing in Australia by Indian companies in this sector, who now may have to resort to take equity stakes in already operating mines whose regulatory approvals are in place.

Sector Representative Contribution: Adani in Australia

- Adani is the largest Indian investor in Australia and has already made ~USD 1 billion direct investment in Australian projects.

- Adani has selected Townsville in North Queensland as its regional headquarters for the Carmichael Mine and Bowen for port and rail. Adani Australia currently engages more than 300 work-force across its businesses.

- Adani is involved in green-field mining and rail projects (Carmichael Project) and is also operating a well-established major port at Abbot Point in Northern Queensland. In addition, Adani has developed a 65MW solar farm in regional Queensland.

Carmichael Project

- The Carmichael Project is based in Galilee in Western Queensland. This Basin has one of the world’s largest coal reserves and produces high quality coal.

- Adani Australia embarked on an investment into development of this mine in 2010.

- The Carmichael Project involves the construction of a thermal coal mine in the Galilee Basin and a 200km multi-user rail line linking the mine site with the existing rail network to Abbot Point Port.

Carmichael Coal Mine Production per Annum

- The Carmichael mine will produce 10 million tonnes of coal per annum in stage one.

Carmichael Rail Network

- The Carmichael Rail Network is being built to support the transfer of coal from the Carmichael mine to the Port of Abbot Point.

- The Carmichael Rail Network will be approximately 200km long, connecting to the existing rail network to provide a seamless freight transport connection between the Carmichael mine to the Port of Abbot Point.

- The Carmichael Rail Network was recently redesigned to link into the existing rail network, reducing costs and accelerating project development. The narrow- gauge rail will ensure the capability to manage the Carmichael mine’s 10 million tonne yearly production rate.

Abbot Point Operations

- Located north-west of Bowen in Queensland, the Port of Point Abbot is Australia’s most northerly coal port, with near 200 direct employees including contractors. The port is operated by Abbot Point Operations Pty Ltd (APO), a company of the Adani Group.

Adani Renewables Australia

- Adani Renewables Australia is striving to be a leading supplier of renewable energy in Australia.

- The business currently has 300MW of solar power projects under development: Rugby Run Solar Farm, located near Moranbah in Queensland and a second solar project 10km from Whyalla in South Australia.

Rugby Run Solar Project

- The Rugby Run Project located near Moranbahin Queensland is under construction and with commissioning from December 2018.

- Rugby Run Solar Farm will supply 65 MW of renewable power in phase 1, with the capacity to expand up to 170 MW.

- Adani has sold 80% of the energy generated through a power purchase agreement. The balance 20% will be sold on the spot market.

- More than 247,000 panels have been installed, which will generate 185,000 MWh of power each year from stage one.

Whyalla Solar Project

- The Whyalla Solar Project is located approximately 10 km from Whyalla, in South Australia.

- Development approval was granted in September 2017, with pre-construction approval granted in August 2018.

- Adani Renewables Australia is currently in commercial negotiations for power purchase agreements.

- Whyalla Solar Farm will deliver up to 140 MW of renewable power and generate up to 300,000 MWh of power each year.

Opportunity for India

India imports ~227 million tonnes of both thermal and coking coal to meet its domestic demand. 85-87% of coking coal requirements in India are expected to be imported till FY23, as a consequence of the growth in production of steel in India.146

Australia’s total export of coking coal in 2018 was 382 million tonnes. Of this, the largest export was to the following:

- Japan, which declined from 119 million tonnes to 116 million tonnes.

- China, which declined from 91 million tonnes to 87 million tonnes.

- India, which increased from 45 million tonnes to 48 million tonnes

India’s imports from Australia have therefore been growing.

A comparison of unit rates for Australian exports to the top 3 destinations shows that world average is USD 123/T. The unit rates for Japan are USD 119/T, China is 114/T, whereas India is at USD 153/T. Historically, India’s coal imports from Australia have been at higher rates than Japan or China. Even the 4th largest importer of coal from Australia, South Korea, has a better import rate at USD 112/T.147

Given India’s high dependency on Australia for its coking coal requirements (48 million tonnes) and in order to sustain the imports from Australia at the current levels, better rates should be negotiated between India and Australia for coking coal imports. The Indian Government should evaluate setting up an organization for centralized procurement of coal to cater to majority (60-70%) of the Indian requirement. This will enable Australian export companies to offer volume discounts and offer competitive rates in line with the rates offered to other countries.

Therefore, from the point of view of enhancing raw material security, India can secure its long- term coking coal supplies from Australia partly by acquiring equity stakes in coal assets and partly by entering into short/ long term contracts. Moreover, Coal India Limited can play a significant role in the acquisition, development and operation of coking coal assets in Australia to assist in importing the required produce to India.

Opportunities in Coal Mining

Opportunities in coal mining identified by the Ministry of Power, Ministry of Coal (MoC), NTPC and Coal India Limited are as follows:

- Adoption of best technological practices of Australia with respect to coal mining for the benefit of thermal power plants in India.

- Adoption of best practices of Australia with respect to real time on-line monitoring of coal quantity and quality supplied to the thermal power plants

- Adoption of best practices of Australia with respect to fly-ash management and noise-less operation of thermal power plants

Iron Ore

Growth of the sector in Australia

Up till 1960, Australia believed that it lacked adequate resources of iron ore for domestic use and hence put up trade restrictions on the export of iron ore. In 1960, with the discovery of large iron ore deposits at Mount Whaleback and exploration efforts of the Bureau of Mineral Resources (now Geoscience Australia), iron ore mining started picking up pace. Australia started selling iron ore, initially to Japan and later to China, to become one of the biggest global suppliers of the metal. Australia is the world’s largest iron ore exporter, exporting 829 million tonnes in 2017.148

Australia’s potential

In 2016, Australia had 49,588 million tonnes of EDR115 of iron ore, accounting for 29% of global iron ore reserves. With mine production of 858 million tonnes in 2016, Australia accounted for 38% of the global iron ore production. This makes Australia the number one ranked nation in both resources and production of iron ore.149

Recent investments in Australian iron ore industry

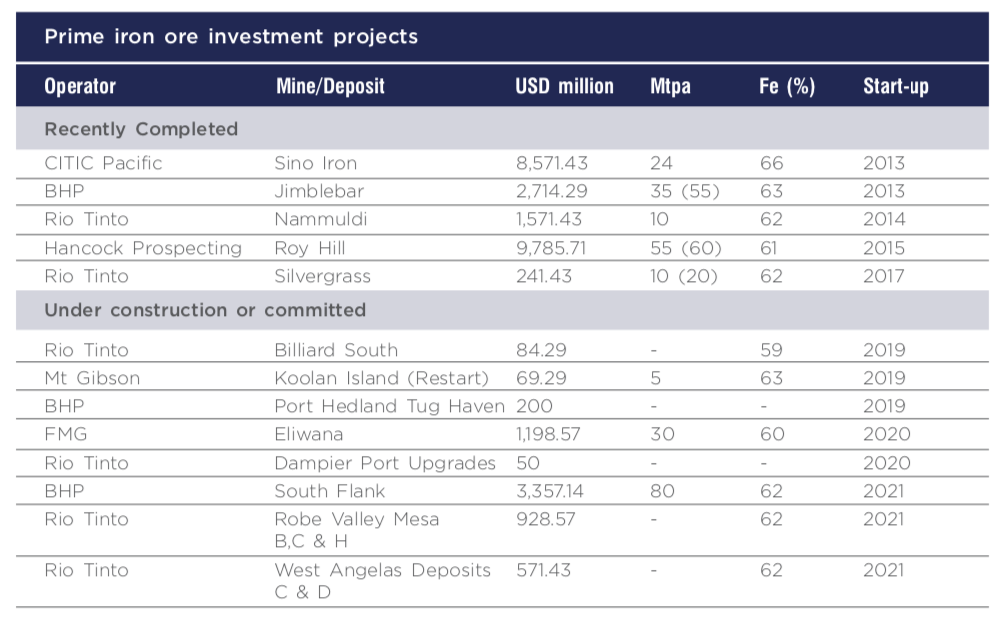

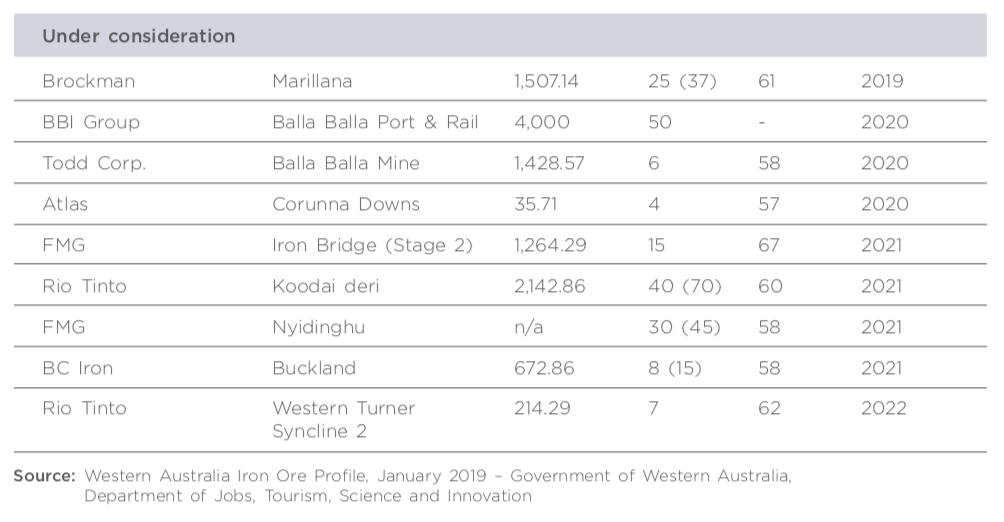

In 2018, Australia’s three biggest iron ore miners, BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue, announced plans to develop mines in the same region, indicating a strong future global demand scenario.

In June 2018, BHP along with Mitsui and Itochu invested USD 3.4 billion into South Flank project in Western Australia. The Yandi mine, which is going to be shut down, will be replaced by the South Flank project, which is scheduled to become operational by 2021, with a minimum life of at least 25 years. The project is expected to produce 80 million tonnes of iron ore a year, which is equivalent to almost one third of BHP’s current production in the Pilbara region.150

Rio Tinto is expected to develop its most technologically advanced mine after receiving permission from regulatory authorities for a USD 2.6 billion investment in the Koodaideri iron ore mine, Western Australia. The mine will have a capacity of 43 million tonnes/ annum after completion.151

Fortescue Metals Group has committed USD 1.27 billion (AUD 1.7 billion) to build a new iron ore mine in Western Australia called Eliwana. The new mine will replace Firetail mine, which is nearing the end of its life. The mine is expected to produce 30 million tonnes/annum and will have an overall capacity of 50 million tonnes/annum with a life of ~24 years.152

Other key recent investments in iron ore industry are in the table below:

Key geopolitical developments

As China is the largest global consumer of iron ore, Australia has increased its share in the Chinese iron ore imports from 43% in 2010 to 62% in 2018.153 This increase in share is due to a large increase in iron ore production by mining giants such as BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals Group in Western Australia. Chinese steel production is heading for a slowdown and many analysts believe that Australian exports to China, that have peaked, will either stabilize or slightly decline going into the future.

With its exit from the coal industry, Rio Tinto has shown a growing focus in iron ore mining with increasing investment in new projects and expansion of current projects in Australia.

Opportunity for India

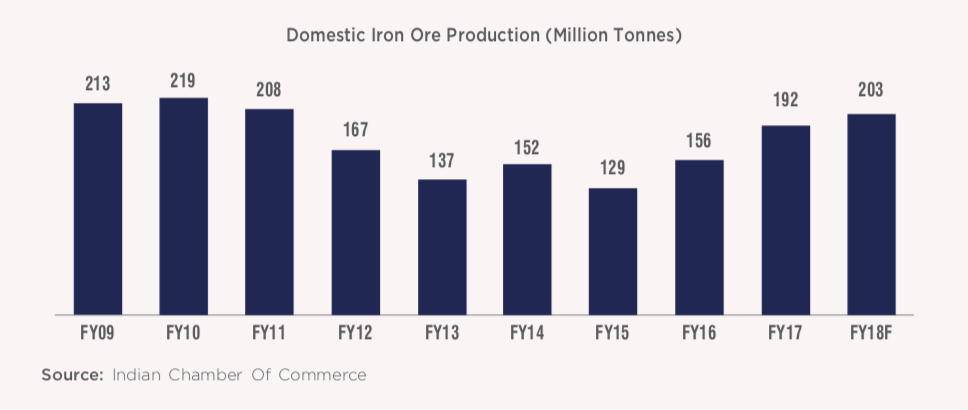

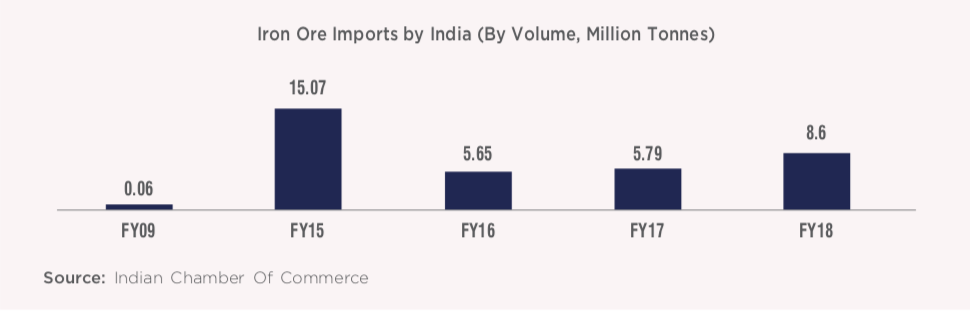

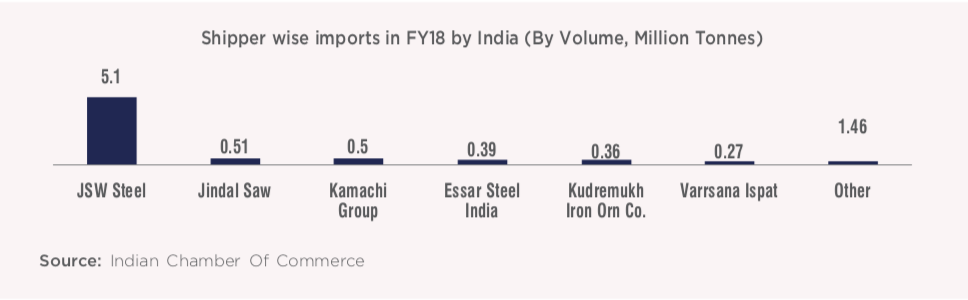

The demand for iron ore in India has been increasing. Though domestic iron ore production was strong in 2017, the domestic supply growth is expected to slow down. This is on account of shutting down of mines in Odisha (with capacity of 20 million tonnes) due to non-payment of fines by the miners154 and the cancellation of 88 renewed mining leases in Goa.155 Further, despite having enough reserves to be self-sufficient in iron ore, Indian iron ore miners face challenges in extracting the complete value from a mine due to illegal mining, Government bans, higher domestic freight cost, lack of infrastructure and lack of economies of scale.156 Another key factor that can potentially lead to an increase in iron ore imports is the increase in production of steel where iron ore is used as a key raw material for making steel. A few established Indian steel manufacturers, such as JSW Steel, are looking at expansion of existing facilities, which will lead to an increase in the iron ore requirement in India.157

All these factors have led to a gradual increase in imports of iron ore over the last 3 years to reach 8.6 million tonnes in FY18. It is further expected to increase by 60% in FY19 and to reach 15 million tonnes.158

Given the fact that Australia accounts for about 28% of the global iron ore reserves with EDR of 49,588 million tonnes,159 Indian iron ore miners could evaluate opportunities in Australia to meet domestic demand as well as increase their iron ore exports.

Copper

Growth of the Sector in Australia

Copper was first discovered in Australia in 1842 in South Australia.160 This led to an influx of miners who developed copper mining across the region, which is now called the “Copper Coast”. In the 1860s, South Australia was referred to as the “Copper Kingdom” as it had some of the largest copper mines in the world. In 1975, the Olympic Dam mining site was discovered and 20 years later, Olympic Dam became the second-largest copper producing region in Australia after Mount Isa.

The exports of copper ores and concentrates (metal content) from Australia grew at a CAGR of ~6%, from 400kt in 2007 to 531kt in 2012. This was mainly due to the rapid increase in construction, infrastructure and manufacturing activity in China.161

Australia is the fifth largest producer of copper and is home to 12% of the world’s economic resources of copper after Chile.162 As of 2016, the country had 34 operating mines and its annual production stood at 948 Kt. The country exported 1,817 kT of copper ore and concentrates to the world in 2018.

Australia’s potential

Australia has a high grade of copper, well-established supply chains and infrastructure, an abundance of world-class geological data as well as a highly skilled and progressive exploration sector. Australian companies can be valuable contributors to the global supply chain. In terms of regulations, South Australia provides strong Government support and is known to be a low risk jurisdiction for conducting mining activities.

Recent investments in Australia

BHP plans to significantly increase its copper production by 75%, from 200,000 tonnes/ annum to 350,000 tonnes/annum, at its Olympic Dam site. The company is considering an investment of ~USD 3 billion for the project. The company also invested more than USD 600 million in FY18 into copper operations with focus on underground infrastructure and above ground processing operations.163 OZ Minerals extended the life of its Prominent Hill copper mine to 2030, after securing a 2% increase in underground ore reserves. This enabled the company to continue its production of 3.5-4 mtpa till 2030. The company is expected to focus on a series of project developments in 2019.164

Key geopolitical developments

In 2018, copper prices were volatile and were dragged down by geo-political uncertainty. The threat of the US imposing tariffs on Chinese goods further fueled uncertainty. China is one of the key importers of Australian copper and the economic developments in China have a crucial bearing on the prices of copper. Since China is expected to fuel the demand for copper in the future, the prices, given the risks, are expected to increase.

Opportunity for India

The Indian copper demand is met through copper ore production from the Indian mines as well as imported metal ores. India has limited copper resources (~1.8% of the world copper reserves) as compared to countries such as Chile (22%), Australia (11%) and Peru (10%).165

Mining of copper in India is mainly covered by Hindustan Copper Limited (HCL) and other private players such as Hindalco Industries and Sterlite Industries that import copper concentrates. These three players primarily dominate the copper market in India. While HCL is the only vertically integrated player in the country, Hindalco and Sterlite have port based smelting and refining plants. Further, India’s refined copper supply in 2018 was adversely affected by the decision to shut down Vedanta Sterlite’s copper plant in Tuticorin, which accounted for 48% of the country’s output. Thus, India’s refined copper output is forecasted to drop to 540kt in FY19 from 843kt in FY18, which may require it to import copper.166

As a result, there exists an opportunity for India to invest in existing mines in Australia to cater to the growing domestic as well as global demand. Indian copper mining companies and end-user companies could explore the option of acquiring a stake in Australia’s copper mines to cater to India’s growing demand.

Unconventional gases and LNG

Australia’s Potential

Australia has large reserves of unconventional gases. These gases include tight gas, coal seam gas and shale gas. Australia has 35,905 PJ (33 Tcf) EDR of coal seam gas, 65,529 PJ (60 Tcf) sub EDR and is also estimated to have a large base of unexplored coal seam gas reserves. The life of the reserves as per the existing production rates is expected to be 150 years.167 Coal seam gas production accelerated in the 2000s and today, constitutes 12% of the gas production in Australia.

Shale gas production is in the nascent stage and is an upcoming industry. Australia is estimated to have a total shale gas EDR of 437 Tcf, equivalent to the amount of domestic gas that could be used in Australia for 400 years.168 It has been estimated that the shale gas resources present in Australia are two times that of the traditional energy resources. Majority of the shale gas reserves are expected to be present in Canning basin of Western Australia, ~235 tcf.

Opportunity for India

India’s production of crude is small as compared to its energy demand. With energy demand growing in future, the use of unconventional gases can assist India in meeting its energy needs. Indian energy companies can explore the opportunity of equity investments/joint ventures with Australian companies to obtain unconventional gases to cater to India’s growing needs.

India has set a target to raise the share of natural gas in the overall energy sector to 15% by 2030, from 6.2% currently in order to reduce the share of hydrocarbon fuels. India thus offers a large energy market and Australia is rich in natural resources such as LNG, which is complementary to India’s ‘gas- based economy’ agenda. India imports ~22 MT of LNG. Total imports have grown from 14 MT in 2014 to 22 MT in 2018, at the CARG of 12%. India currently imports ~1.44 million tonnes of LNG from Australia. India also imports ~10.7 million tonnes of LNG from Qatar under two long term contracts. Besides Australia and Qatar, other suppliers for LNG include Nigeria (3 million tonnes), Angola (1.4 million tonnes) and Oman (1.1 million tonnes).

Australian prices for imports of LNG have historically been the highest at USD 416/T as compared to USD 394/T from Qatar, USD 344/T from Nigeria and USD 397/T from Angola. This was partly due to non availability of a terminal on the East Coast of India to receive LNG from Australia. Until now, Australian LNG was being shipped to India’s West coast and hence was pricier as compared to LNG from Qatar, partly due to logistics costs. Australian LNG deposits are located in Western Australia and Northern Territory. With the development of Ennore and later other ports on the East Coast of India, there could be an opportunity to ship LNG from Australia. Australian companies could then look at India for supplying LNG at lower prices than what is supplied to other countries as a possible diversification strategy.

There is also significant potential for technical collaborations between the two countries on conventional gases such as liquefied petroleum gas, fuel oils, petrol, diesel, kerosene, asphalt base and others.

Mining Equipment, technology and services (METS) industry

Australia Potential

Australia provides the best in class mining equipment, technology and services (METS). Australia has perfected mining technology, required to perform mining efficiently in tough conditions, while ensuring high productivity of mines within stipulated environmental standards. A stable socio-political scenario, presence of skilled professionals and consistent growth in the economy has resulted in high demand for Australian METS from various countries across the world.

Australia is home to numerous METS companies, which provide innovative and technologically advanced services to the mining industry, most of which are SMEs. Some of the prime companies operating in the industry are Dingo Software, Micromine, GroundProbe, UGM and RUS mining, Orica, etc.

The METS industry also has a leading industry body called Austmine, with more than 560 corporate members including companies , subcontractors, software vendors, original equipment manufacturers, technology companies and support services. Austmine supports and promotes the METS sector by encouraging innovation, facilitating collaboration among various stakeholders and providing growth opportunities.

Additionally, METS Ignited, an industry-led growth center for the MET sector, has also undertaken initiatives to improve productivity and research in Australia’s MET sector. In collaboration with Austmine, CSIRO, the federal Department of Industry, Innovation and Science and the Queensland Government, METS Ignited developed the METS 10 Year Sector Competitiveness Plan, in 2016, to spearhead innovation and development across Australia’s mining industry.169 This plan aims to extend collaborative opportunities, bilateral relationships and commercial opportunities within the global mining ecosystem to position Australia as the hub for mining innovation.

Source: Core Resources website

Opportunity for Indian mining industry in METS

The Indian mining sector has scope for further development. Its contribution to India’s GDP is stagnant at 2.5% for the past ten years.170 With increasing growth and domestic demand for mining resources and activities, India faces a pressing need to increase productivity in its mining sector.

In line with this growing demand, Coal India Limited(CIL) is poised to grow from a 607 Mt to a 1 Btcompany within the next few years. For successful implementation of this growth prospect, CIL will be required to adopt the best of technology and management practices followed in the global coal mining industry including state of the art equipment and services for production of coal.

The Indian mining sector needs improvements and further development in certain areas, which include:

- High ash content in coal: Indian coal has higher ash content, which reduces the power generated in thermal power plants. The ash content in Indian coal is 25-45%171 when compared to Australian coal, which has an ash content of 12-20%, creating a need for beneficiation and coal washeries.

- Inadequacy of equipment: Most of the mine developer-cum-operators (MDOs) rely on small scale equipment and require large scale technology.

- Shortage of skilled labour: India has a requirement of skilled mining engineers who are required to support the sophisticated mining equipment.

- Thermal power plant inefficiencies: The technology used in thermal power plants is sub- optimal with average efficiencies of 31-33%.

- Environmental and safety concerns: India has inadequate clean coal technology, thereby contributing to pollution.

As India’s mining sector continues to grow, owing to rapid modernization and infrastructure development, the requirement of mining equipment, technology and services will increase across the value chain. Australia has the potential to address all the aforementioned challenges that India faces with its cutting-edge technology, sustainable mining practices, geo-scientific research techniques and skilled workforce.

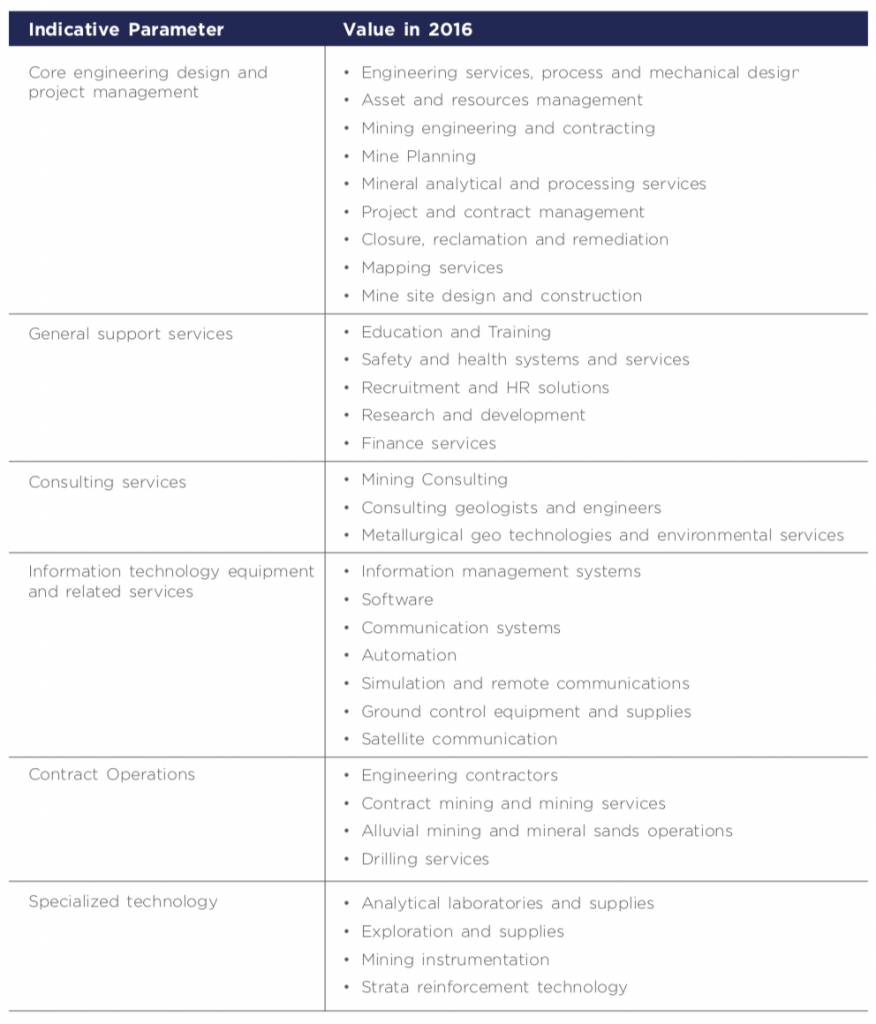

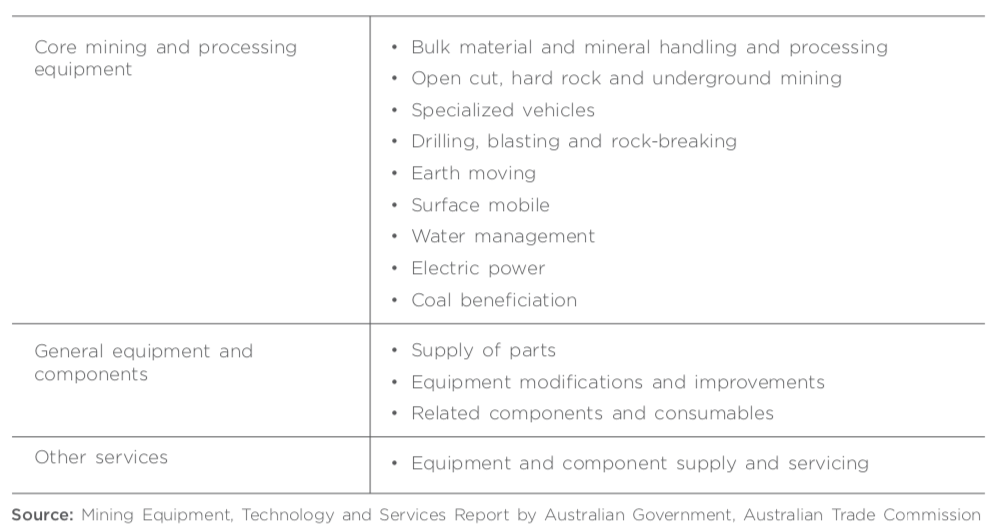

Australia offers a wide range of METS products and services, which have been highlighted below:

Australian firms operating in the METS sector are competitive across the mining supply chain and are flexible across different commodities. Australia has a competitive edge across various supply chain areas such as exploration, mine development and mineral processing, engineering, environmental management, mine safety, R&D and education & training.

The mine-developer-cum-operator (MDO) model is popular in India, where the entire responsibility of developing a mine is subcontracted to a contract miner, who operates the mine on behalf of the mine owner. The key players in this segment include Essel Mining and Industries Limited (EMIL), Thriveni Earthmovers, Sainik Mining and Allied Services, AMR India Limited, JSW Energy, Adani Enterprises, etc. Indian MDOs/ miners can invest in Australian METS companies to form joint ventures in order tackle challenges of low productivity and quality to access advanced Australian technology and best practices.

In addition, India can also manufacture and export mining equipment to meet excess demand from Australia. The availability of labour at a reasonable cost, combined with a host of Government initiatives for manufacturing, make India an extremely attractive manufacturing destination. There are known examples of select Australian companies that have invested in setting up plants in India for manufacturing equipment to meet the Australian demand for specification pressure vessels for the oil industry. These companies use Australian technical expertise to manufacture such equipment to meet Australian as well as global oil and gas industry demand. Additionally, Indian manufacturers of mining and heavy equipment including Ashok Leyland, BEML, HEC, Eicher, L&T etc. can also similarly benefit from collaborations with the METS industry in Australia through Australian companies such as Austmine. This will further support the “Make in India” initiative of the Government of India.

Given that the Neyveli Lignite Corporation India Limited (NLCIL) has a broad base of knowledge in depressurization of ground water aquifer for lignite mining and the workings of specialized mining equipment such as Bucket Wheel Excavator and belt conveyors, NLCIL’s expertise could be applied in the brown coal basin of Australia.

For instance, Coal India Limited is currently engaged with Australia via a government to government initiative with CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) on capacity development in Coal Mine Methane (CMM). CIL has also procured orders for equipment and services from Australian companies related to GPS based fleet management systems in OC mines (Leica Geosystems), slope stability monitoring in overburdened dumps through ground probing radar (Ground Probe), mine planning and design software (Minex, Surpac, Vulcan), explosives (ORICA), Dust suppression solutions (COOEE DUSTBLOC), underground diesel vehicles (Valley Longwall). Currently, discussions on procurement of other products such as dumper turntable, in-motion dumper weigh bridge, screening attachment in shovels etc. are in progress.

Since 2019, the Government of India has planned significant diversification and induction of technology in coal mining. The Government is also planning to introduce private sector in the coal mining sector in India. Underground Coal Gasification (UCG) is one such technique that has generated significant interest from the Government. UCG is a method of converting coal still in the ground to a combustible gas that can be used for various uses, including power generation. UCG presents several advantages to conventional coal mining in the form of reduced mining and transportation along with reduced environmental impacts. UCG requires significant capital investment and technological upgrades to ensure commercial viability.

Mining is one of the riskiest and most hazardous occupations in the world. The safety standards of India’s mines, though not as stringent as the standard operating Procedures (SOPs) adopted in Australia, have been progressively improving and the Directorate General of Mine Safety (DGMS) has been responsible for carrying out initiatives for mine safety and mine inspection in India. DGMS is also working on safety codes for protection of contract and temporary mine workers. Despite these efforts, inadequate infrastructure and lack of training and awareness have put 251,700 employees in the sector at a significant safety risk. Australian companies such as AusDrill, have extensive programs focusing on mine safety and training. Thus, India could enhance its capacity for training in MET skills and occupational safety by collaborating with such Australian companies. For this purpose, India and Australia have been making progress towards such collaborative models and in early 2019, a MoU was signed between DGMS and Safety in Mines Testing and Research Station (SIMTARS) for cooperation in occupational safety. SIMTARS is a commercial business unit of the Queensland Government Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, which provides a range of services to improve safety and health across the mining industry.

There is also a requirement of skilled manpower for mining operations in Australia. In Australia, mining operations are highly mechanized. The skill sets of Indian workforce can be mapped with the Australian workforce to enable Indian workforce to find adequate employment at Australian mines. Post their exposure to mechanized mining in Australia, these skilled resources can dramatically improve productivity and safety standards in India.

Opportunity for Australian investment in India in METS

As per Invest India, the market for Earth-moving and mining machinery in India is valued at USD 3.3 billion. The mining equipment market has been growing in the last few years. The demand for mining equipment in the country is largely driven by increased coal mining along with an increase in quarrying and infrastructure projects. The government has laid extensive focus on upgrading this sector by permitting 100% FDI via the automatic route and through programs such as National Capital Goods Policy, 2016. This sector in India thus presents significant opportunities for Australian investors across the mining value chain that include enhancement of skill development in installing, operating and manufacturing advanced extraction technologies as well as investing in advanced drilling, sensing, sorting and processing technologies.

Sector Representative Contribution: Access Petrotec & Mining Solutions

Access Petrotec, established in 2009, is a Perth-based Australian company that offers engineering services and equipment solutions to the oil and gas, mining and infrastructure industries. The company was founded by two entrepreneurs, Peeyush Mathur and Vinod Gupta, who migrated from India to Perth. Within the mining industry, Access Petrotec offers a range of customized equipment packages including pressure vessels, skid mounted process equipment, submersible pumping systems, chemical dosing skids, air compressors and dryers, nitrogen plants, material handling systems and lube oil skids.

Access Petrotec provides an ideal mix of cost-effective manufacturing based on their facilities set up in India and compliance with the International standards of engineering. In India, in partnership with Baroda Equipment & Vessels, they manufacture high-quality cost effective pressure vessels, heat exchangers and other process equipment. Access Petrotec also buys a range of submersible pumps, sold under the ‘Darling’ brand in India for mine dewatering, waste water applications, etc.

In addition, they have also collaborated with Techpro Engineers Private Ltd in Kanpur to provide tailor-made equipment solutions to their clients.

In 2016, Access Petrotech also expanded its operations in the renewable energy sector through the establishment of a new subsidiary company, Australian Energy Storage (AES), in India. Since 2017, AES has run a small- scale assembly line for its battery packs in Vadodara. Further, AES has identified the Indian cities of Vadodara, Ahmedabad, Indore, Jaipur, Gurgaon, Kolkata, Jamshedpur and Agartala as its prime target for its e-rickshaw battery solutions (selected based on high demand and usage of E-rickshaws).

Collaboration with Australian federal bodies and universities

Australia has the reputation of developing leading edge, new equipment and services for the mining sector. The country is home to best-in-class institutions such as the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), National Science agency, universities and centers of excellence. Technical collaborations between Australian mining research centers and universities hosting research on Indian mining, as well as private Indian mining companies, could provide significant upgrades to India’s mining sector, in terms of infrastructure, technology and expertise. Australia has several research centers and university excellence programs where their corresponding Indian counterparts can extend collaborative fronts. These institutes/ universities include Geoscience Australia, Australian Centre for Geo-mechanics, Mining Research Centre at the University of Wollongong (UOW), Mining & Energy Research Centre at The University of Adelaide, Minerals and Energy Research Institute of Western Australia (MERIWA), Sustainable Mineral Institute at The University of Queensland, etc., amongst others.

Source: News Articles; Exploration and Mining: Opportunities in India, Ministry of Mines

Indian mining companies can also collaborate with Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO)177, an independent Australian federal Government agency responsible for scientific research, on their various mining research projects to leverage technologies and to scale up research. CSIRO offers a central platform to the Indian Government and corporates to access information and subject matter expertise on technologies that are ready to be commercialized. Furthermore, they also offer opportunities for investments by providing access to niche projects that are underway.

Source: SCCL for increasing coal production seeks cooperation from Australia for the purpose, The Hindu, 2019

Curtin University’s Western Australia School of Mines’ has a mining operations training program, which is one of the top ranked mining programs in the world. Australia also has other universities whose mining programs feature amongst the top 20 in the world, namely, University of Queensland, University of New South Wales (UNSW Australia), University of Western Australia, University of Melbourne and University of Adelaide.178 India can explore collaboration with these institutes, both at the corporate as well as at the Governmental level.

Recent Chinese and Japanese investments

Recent Chinese and Japanese investments

Mining was the largest sector for Chinese investments in 2017 attracting investments worth AUD 4.6 billion (USD 3.1 billion). The investments were driven by a ~AUD 3.4 billion (USD 2.3 billion) coal mining deal and continuing investment focus in lithium.

China has been increasingly focusing on lithium related projects, which is a primary material in batteries used in electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. Some recent investments include:

- In 2017, Talison Lithium, which has 51% of its ownership with Tianqi Lithium, invested~AUD 320 million (USD 214 million) to double the capacity of the Greenbushes Lithium mine, which supplies ~40% of world’s Lithium.

- Tianqi Lithium made a strategic decision in 2016 to diversify lithium processing away from China. To build processing capabilities in Australia, it made a ~AUD 400 million (USD 268 million) investment for construction of a large-scale processing plant in Kwinana, Western Australia with annual production of 48,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide.

- Tianqi Lithium has also invested ~AUD 700 million (USD 469 million) in a lithium hydroxide processing plant in Western Australia. Tianqi made an initial investment of ~AUD 400 million (USD 268 million) in 2016 for an initial production capacity of 24,000 tonnes per year. This ~AUD 300 million (USD 201 million) facility is expected to be completed in2019.

- In 2015, Jiangxi Ganfeng Lithium made an ~AUD 18.54 million (USD 12.4 million) investment in Australian Lithium mining company Neometals.

- Baosteel Resources/ Aurizon Holdings made an ~AUD 910 million (USD 610 million) investment in Aquila Resources Limited, which has assets with copper, zinc and gold deposits.

Investments by Japan

From the 1960s, Japanese investments have pioneered the growth of Australia’s mining and resources sector. Investments across the Pilbara Region in Western Australia, the Hunter Valley in New South Wales and the Bowen Basin in Queensland, opened these regions to the global markets.

Some recent key investments by Japanese players include:

- Toyota Tsusho Corporation acquired a strategic stake in Orocobre, a Lithium mining company, for ~AUD 292 million (USD 196 million). The investment will primarily be used for the expansion of the Olaroz project to increase the annual capacity from 17,500 tonnes of LCE to 42,500 tonnes of LCE. Tsusho will also secure a long-term supply of lithium products to cater to the growing market demand.

- Japanese trading house Mitsui has a signed a take-off agreement with Kidman Resources, which has a 50% stake in the Earl Grey lithium project at Mount Holland, 400 km east of Perth. Kidman aims to start production in second half of 2019 and plans to ship the concentrate to the lithium hydroxide refinery at Kwinana.

- Japanese trading house, Sojitz and the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation provided ~USD 250 million in capital to help Lynas, the world’s only major rare-earth producer after China, to boost its production of rare earth minerals.

- Inpex corporation, Japan’s largest oil and gas exploration and production company, is leading a USD 34 billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) project in Icythys, Western Australia. Japan shipped its first LNG cargo in 2018 and production in the project has reached its full capacity of 8.9 million tonnes a year in 2019.

Implications for India

Key economies such as China and Japan are actively investing in Australia’s resources to meet the potential demand for their domestic consumption. India with its population of 1.3 billion179, GDP of 2.7 trillion and an expected growth of 6-7% over next five years would need to collaborate and invest in Australia’s mining of resources to meet its growing domestic needs.

Encouraging investments by Australian companies in Indian mining industry

India too has a vast potential in its domestic mining industry. India has abundant mineral resources and is the key producer of many minerals. In 2017, India was ranked as the fifth largest producer of iron ore, fourth largest coal producer and third-largest chromium producer. India is also a key producer of bauxite, manganese ore and other smaller minerals such as talc, steatite and barytes . Mining sector contributed ~2.5% of India’s nominal GVA in FY18, 14% of India’s overall exports and 30% of India’s overall imports180. High public spending on infrastructure-railways, metro projects, roads and ports, growing urbanization-100 smart cities planned by 2020 and stable medium-term outlook in the automotive industry is expected to lead to high demand for mineral resources in India. Further, the Government of India has taken measures to ease the mining regulations to attract foreign investments in India. Some of the key measures taken by the Government are:

- 100% FDI under the automatic route has been permitted in the coal mining sector.181

- Adoption of transparent, seamless and simplified procedures to grant mineral concessions and to facilitate exploration processes. E-Governance, IT enabled systems, awareness and information campaigns have been incorporated182.

- Facilitation of clearances through an online public portal in a time-bound manner. Further, state Governments will endeavor to auction mineral blocks with pre-embedded statutory clearances182.

- Proposed a long-term export import policy to provide stability and incentivize private sector to invest in large scale mining activity182.

The mining sector in India is expected to witness major reforms over the next few years owing to the Make in India campaign, Smart Cities Program, rural electrification, renewable energy projects under the National Electricity Policy as well as as increase in infrastructure development. With robust growth in domestic demand and favourable Government policies, the mining sector presents opportunities for Australian companies to invest in resource mining and exploration in India.

In the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, several reforms were announced by India’s Finance Minister to revive the Indian economy in mid-May 2020. Commercial mining of coal by the private sector will now be permitted. This will be carried out on a revenue sharing mechanism rather than a fixed rupee/tonne regime. Further, an investment of INR 500 billion (USD 7.14 billion) has been proposed for coal shipment infrastructure, including mechanized transfer of the fuel from mines to railway sidings in India.

Recommendations

- The Indian Government and the private sector should evaluate entering into offtake agreements/investments/joint ventures with Australian mining assets / mining companies to secure access for India’s critical mineral requirements and across resources such as coal, iron ore, copper, gold, potash, phosphate etc.

- The Indian Government should evaluate setting up an organization for centralized procurement of coal to cater to majority (~60-70%) of the Indian requirement which could be a demand aggregation for Government and private imports. This will enable Australian export companies to offer volume discounts and offer competitive rates in line with the rates offered to other countries.

- Indian institutes / corporates and Government bodies should encourage partnerships with Australian institutes to facilitate joint research and training and knowledge transfer programs in the following areas: Mine safety and technology applications, mine exploration and mapping in India, student exchanges between Indian institutes such as IIT-ISM and Australia’s mining universities, encouraging two-way consultation programs for specific mining applications and issues.

- Encourage Australian companies to invest in the mining and METS sector in India.

108 Australia Bureau of Statistics, no. 5204

109 Australia Bureau of Statistics 5302 and 5368

110 Labor Market Information Portal, Australian Government

111 The Early Mining History of Australia’s Most Famous Goldfields, 2018

112 Australia Bureau of Statistics

113 Geoscience Australia

114 Geoscience Australia

115 EDR implies Economically Demonstrated Reserves

116 Australia’s identified mineral resources 2017, Table 3

117 Australia’s Identified Mineral Resources 2018, Geoscience Australia

118 The lithium-ion battery value chain, Austrade

119 Australianmining.com

120 Mineral Resources Limited Website

121 Lithium-Ion Battery Value Chain, Austrade, December 2018

122 Lithium-Ion battery recycling presents a $1,000 million opportunity in India, Economic Times, 2019

123 India Lithium-Ion Battery Market - Growth, Trends and Forecast Report, 2018, Research and Markets

124 Spearheading India’s Mobility Transformation – In conversation with Amitabh Kant, Auto Futures, 2019

125 Companies line up plans for lithium-ion batteries production, Economic Times, December 2018

126 Tata Chemicals may make lithium-ion cells, Mint News, July 2019

127 USGS Mineral Resources Program

128 Aeon Metals press release

129 Australia Investing News, Clean TeQ website

130 Australia Mines Limited website, Australiamining website

131 Thomson Reuters

132 Independence Group website

133 Western Areas website

134 Nickel, Indian Minerals Yearbook 2017

135 India scrambles to look overseas for rare earths used in EVs, Nikkei Asian Review, 2019

136 Australia in talks to boost rare-earth supply outside China, The Straits Times, 2019

137 Australian coal exports set new record in 2017, 2018, Australia Mining

138 Australia’s identified mineral resources 2018, Geoscience Australia

139 Rio sells Kestrel coal mine for $US2.25b to EMR Capital, Adaro Energy, AFR

140 Rio Tinto agrees sale of Hail Creek and Valeria to Glencore for $1.7 billion, Rio Tinto

141 Rio Tinto completes divestment of Coal & Allied Industries Limited for $2.69 billion, 2017, RioTinto

142 Glencore makes move on Mitsubishi coal assets, 2018, Australian Mining

143 Adani website

144 Adani scales down plans, to self-finance Oz project, The Economic Times, 2018

145 News Articles

146 Coal imports to remain hot, 2018, CRSIL

147 UN Trade Map

148 Global iron ore market well supplied, growth in production ahead — reports, 2018, Mining [dot] com

149 Applying geoscience to Australia’s most important challenges, Australian Government

150 Mitsui to Develop South Flank Iron Ore Mine in Australia , Mitsui & Co., 2018

151 Rio Tinto approves $2.6 billion investment in Koodaideri iron ore mine, 2018, Rio Tinto

152 FMG green lights $1.7b Eliwana with 500 jobs to come, 2018, The West Australia

153 Iron ore’s contribution to Australia’s prosperity has peaked, say experts, 2018, Financial Review

154 Non-payment of fines to shut off 20 mn tonne iron ore capacity in Odisha, 2018, Business Standard;

155 Supreme Court cancels iron ore mining leases of 88 companies IN Goa, 2018, The Economic Times

156 Indian Metals and Mining, Indian Chamber of Commerce

157 SteelMint group-Events

158 Business Standard

159 Australia Benchmark Report 2018, Austrade

160 Australian Government, Geoscience Australia

161 Production, Geoscience Australia

162 Austrade, Australia Benchmark report, Geoscience Australia

163 BHP seeks 75% copper growth project at Olympic Dam, Australian Mining, 2019

164 OZ Minerals pushes for major project growth in 2019, 2019, Australianmining website

165 Ministry of Mines, Annual Report, 2018-19

166 Indian Metals and Mining Report, EY, June 2018

167 Geoscience Australia

168 US EIA, EIA/ARI World Shale Gas and Shale Oil Resource Assessment

169 Launch of a national plan for a globally competitive Australian METS sector at IMARC

170 Press note on provisional estimates of annual national income, 2018-19 and quarterly estimates of gross domestic product for the fourth quarter of 2018-19, Government of India

171 High ash content, Ministry of Coal, PIB, 2018

172 CSIRO

173 Delivering Innovation and Science Excellence, CSIRO website

174 Our Top 10 Inventions, CSIRO website

175 News Releases, CSIRO website

176 The Impact and Value of CSIRO Research 2018

177 CSIRO: Mining and Manufacturing

178 QS university rankings

179 World Bank

180 Coal sector gets nod for 100% FDI; The Economic times

181 National Mineral Policy 2019, Government of India, Ministry of Mines; The point is applicable only for non-fuel and non-coal minerals

182 National Mineral Policy, 2019 approved by Cabinet, Press Information Bureau, 2019

Next topic: