Focus Sectors

Healthcare

Synopsis

The healthcare system in Australia is highly specialized and focuses on tracking the background and history of patients through disease coding and data analysis with a strong emphasis on preventive care and early disease detection.

India’s strengths in tertiary healthcare and low-cost manufacturing as well as Australia’s expertise on research and development in med-tech and bio-tech offer opportunities that could benefit both countries:

The following opportunities have been identified for this sector:

- Adopting Australian healthcare best practices in India

- Collaborating between Indian and Australian hospitals to gain from Australian expertise

- Leveraging Australia’s expertise in creating a developed aged care model.

- Collaborating in cancer detection and research

- Collaborating with Australian med-tech companies

- Collaborating across medical coding and data analytics

- Developing India as a medical tourism hub for Australians

- Collaborating in areas such as healthcare education and training for nurses

- Increasing expert consultations from India

Australian healthcare ecosystem

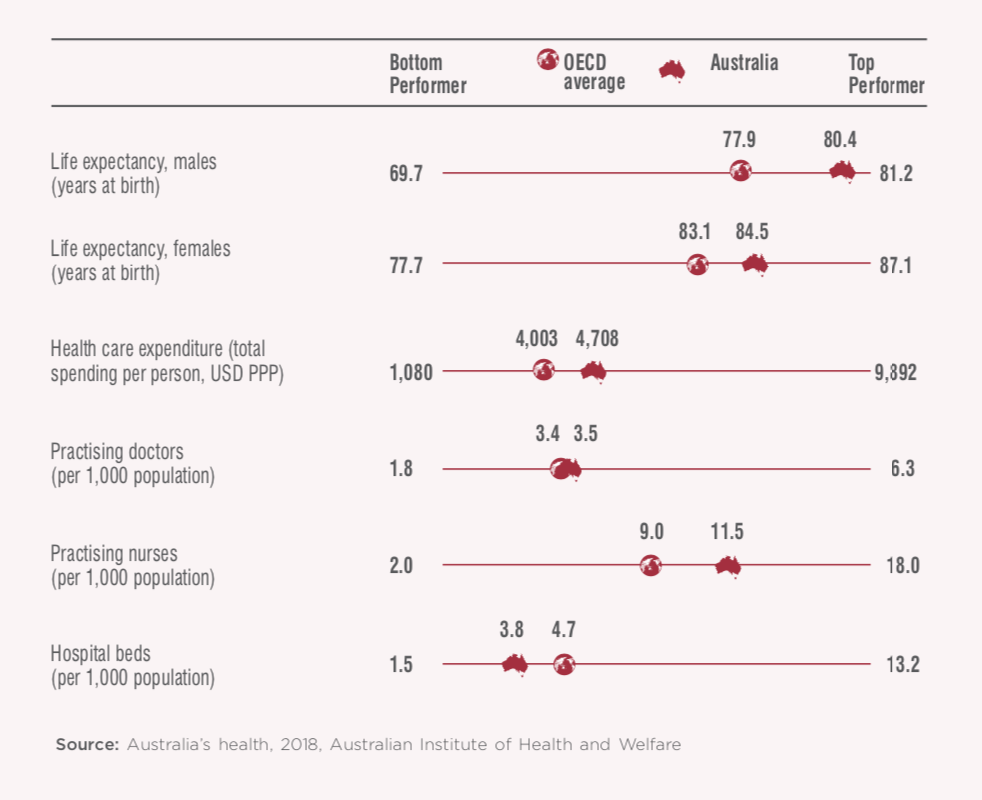

The Australian healthcare system is renowned worldwide on account of significant Government focus, which has resulted in greater access to affordable and quality healthcare. Healthcare in Australia is provided by both public and private players. Australia’s performance on several health parameters is largely in line with OECD averages.

Australia spends 10.3% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on healthcare, which is comparable to that of other developed countries such as the UK (9.7%) and France (11%).258 Over the last few years, the expenditure on healthcare has grown at a faster pace than the overall GDP growth, which signifies the Government’s intent to further develop and improve the healthcare sector.

Traditional healthcare services

The Australian health ecosystem faces challenges from an ageing population along with the burden of chronic illnesses. These challenges are typically long term that need continuous management and have a considerable effect on individuals, their families and care-givers and the health system. The incidence of chronic diseases such as cancer, heart related problems as well as health issues specific to the aged population such as arthritis, dementia, etc., highlight the need for a robust healthcare service network. Australia’s healthcare sector has been successful in providing widespread access to services for the majority of the population. This success can be attributed to the collaboration across different levels of Government (Central, State, etc.) as well as the innovation driven by the private sector.

Primary healthcare

Primary health is at the forefront of Australia’s health care system, as it is generally the primary point of contact for patients. Australians receive primary health care largely from general practitioners (GPs), along with other stakeholders such as nurses, midwives, community health workers and allied-health professionals, who perform a wide range of services. General practitioners (GPs) are central to primary healthcare in Australia.3 There are 1.4 GPs for every 1000 people.259 The number of GP services availed by Australians has steadily risen at approximately 18% in the last ten years to reach 602.7 per 100 people in 2016-17.259

India, in stark contrast to the Australian scenario, suffers from a shortage of primary healthcare service providers. Furthermore, the demand gap in primary healthcare in rural India is even more pronounced since primary health infrastructure, as well as workforce are scarce. This demand gap leads to migration from rural to urban and semi-urban areas to access quality healthcare. While rural India holds 70% of the population, only one third of the country’s healthcare infrastructure is located in these areas.260

In Australia, primary healthcare is well connected to the rest of the healthcare ecosystem, which includes hospitals, secondary care providers and other service providers through Primary Health Networks (PHNs). Australia has 31 Primary Health Networks (PHNs), which are independent Government-funded organizations, managed by a board of medical professionals.261 PHNs partner with Government organizations at both state and territory levels to enhance patient care by aligning and increasing coordination between different stakeholders to avoid overlaps in providing health related services. Primary healthcare providers in Australia can refer patients to access specialist secondary healthcare or directly to hospitals (tertiary healthcare).

Hospital Infrastructure

Australian hospital infrastructure has a mix of public (52% of hospitals) and private (48%) players.262 Public hospitals in Australia are largely funded by the Government and offer a wide variety of high-quality services at no/low cost to patients under the Medicare Scheme. The public hospitals in Australia have a higher capacity than that of private hospitals; thus providing treatment to a larger number of patients in Australia.

Private hospitals in Australia are largely funded by private insurance companies as well as through out-of-pocket payments by patients. The number of private hospitals in Australia are on the rise on account of rising demand as well as increase in private insurance.

Some of the large private healthcare chains in Australia include Ramsay Health, Healthscope Hospitals and Healthe Care, etc. Ramsay Health Care is one of Australia’s largest private hospital networks with a chain of 72 private acute and day surgery units. Apart from its private hospital chain, Ramsay Health also operates in 4 public general hospitals under a public private partnership model in Australia. Healthscope Hospitals is Australia’s second largest private hospital operator with a network of 43 hospitals. It is concentrated specifically around important cities in Australia. Healthe Care is the third largest chain with 36 private healthcare facilities.

Opportunities for Australian investments in Primary Health Care / Healthcare Governance

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has projected an investment of Rs. 5.38 lakh crore (USD 76.8 billion) in India’s primary healthcare over the next 5 years to cater to India’s growing healthcare demands.In addition, the Ministry also projected an investment of Rs. 1.88 lakh crore (USD 26.8 billion) to address shortage of healthcare professionals and Rs. 90,336 crores (USD 12.9 billion) for infrastructure upgrades.

In recent years, India’s healthcare sector has witnessed significant international investor interest. Post the year 2000, 100% FDI under the automatic route for greenfield healthcare projects and 100% FDI under the government route for brownfield projects has been permitted. As per industry reports, private equity investors have invested more than USD 3.4 billion in Indian hospitals between 2004 to 2017. Apart from meeting funding requirements, foreign investments also bring in technology upgrades and new skill sets to the healthcare sector in the country. Further, an upgradation of service levels and facilities is also required to provide a boost to medical tourism in the country. Apart from opportunities for investment in hospitals, India also presents several avenues for investments to Australian healthcare providers, namely in diagnostics, medical devices and equipment industry and for setting up training facilities for healthcare personnel. International investment in the healthcare sector has been largely limited to the higher end of the value chain, namely secondary and tertiary care. Australian investments can assist the Indian healthcare sector upgrade the primary healthcare sector and increase penetration of healthcare services via investment in technologies such as e-healthcare.

Preventive Healthcare and Mental health

Sedentary lifestyles, changing dietary patterns and mounting healthcare costs have necessitated the shift in healthcare from traditional curative models to more preventive ones. Preventive healthcare focuses on taking measures to maintain wellness and overall good health. Increasing expenditure on preventive healthcare is a cost-effective strategy that can vastly improve health outcomes in a country.

Prevention has been a vital part of the Australian Government’s National Primary Health Care Strategy. Immunization and disease screening are key preventive health care measures in Australia. Australia also has extremely effective anti-smoking and road safety campaigns. Given that mental disorders, namely anxiety and depression, are a heavy disease burden on the Australian population, early detection and treatment of mental health disorders are also priorities of the Australian medical system.

India’s healthcare system lays more emphasis on curative rather than preventive healthcare. It is estimated that only 9.6% of India’s overall healthcare expenditure is on preventive measures and the remaining 90% is on the treatment of various illnesses. India has a universal immunization program under which the Government of India provides vaccination to prevent several preventable diseases. Even while this program has been extremely successful in almost entirely eradicating the incidence of polio from the country, the focus of preventive healthcare has still largely been on communicable diseases. India still lacks frameworks for screening and early detection of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Despite NCDs being far easier to detect than communicable diseases, they account for approximately 61% of the deaths in India.263 Early detection through regular health check-ups and screening will not only significantly reduce the incidence of NCDs, but will also materially bring down long-term healthcare costs.

Furthermore, mental health and wellbeing represent some of the most neglected areas in India’s overall healthcare system. While perceptions towards mental health are changing in India, factors such as lack of awareness, social stigma and inadequate access to mental health professionals reflect that the progress of mental health service delivery in India has been particularly slow. India can learn from Australian best practices in mental health service delivery to bring awareness and improve overall management of mental health as well as create delivery systems that support self and family driven care throughout the life-cycle.

Vendors

Pharmacies

Pharmacies play an important role in Australia’s healthcare system. They are the key providers of medicines under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Australia’s retail pharmacy sector is a mix of private pharmacy chains and independent community pharmacies. The ownership of pharmacies in the country is restricted to registered pharmacists. Australia also has restrictions on the number of pharmacies owned by a pharmacist, which differ by state. For example, in Western Australia and Tasmania, the maximum number of pharmacies owned by a pharmacist is 4, in Queensland, NSW and Victoria, this number is 5 and in South Australia, the number is restricted to 6. Large pharmacy chains in Australia have therefore established a network under franchisee models. Leading players in the pharmacy industry in Australia include Sigma Healthcare, Terry White, Chemist Warehouse, Priceline Pharmacies, etc. Australian pharmacies are well-connected and it is estimated that 95% of consumers are within a 2.5 km radius of a pharmacy in state capital cities and 72% in regional Australia.264

In contrast, India’s pharmacies are highly fragmented with a large number of standalone stores. Branded stores and chains account for only 1% of the estimated 0.7 million retail outlets.265 Apollo Hospitals’ pharmacy chain is the largest in India with over 3100 stores.266 Other large pharmaceutical chains in India include MedPlus, Wellness Forever, etc.

Diagnostics

The diagnostics services in Australia can be divided into two segments- diagnostic imaging and pathology services. Pathology services include study and diagnosis of disease through examination of organs, tissues, cells and bodily fluids. Diagnostic imaging includes an array of technologies, such as general X-ray, bone densitometry, mammography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), etc.

Pathology services in Australia are highly consolidated and organized, mainly in the hands of two major players – Sonic Healthcare and Primary Health Care, with a market share of 43% and 34% respectively.267 Diagnostic imaging in Australia is a fragmented sector with multiple small and medium players. However, some of the large players are expanding organically as well as by acquiring smaller practices. In addition to pathology majors, some of the large players in the diagnostic imaging sector are I-MED Radiology and Integrated Diagnostics.

India’s diagnostics services market is fragmented and largely unregulated, especially in tier 2 and tier 3 cities. India has over 100,000 laboratories and only 20% of these are run by organized players.268 A large part of the organised sector’s revenue is contributed by tier 1 cities in India.

Healthcare workforce

The Healthcare and social assistance industry in Australia employed the largest share of the workforce in 2018, with ~1.6 million people representing nurses, doctors (general practitioners and specialists), aged and child care professionals and allied health professionals.269

As per the Medical Board of Australia, there were over 103,000 practicing doctors in the country as of December 2018, of which ~39,000 were purely general practitioners, ~54,000 were general practitioners with a specialty and around ~10,000 were specialists. While Australia has a high density of doctors (3.5 per 1000 people and 4.4 per 1000 people in key cities), there still exist gaps in the supply of medical practitioners in rural and remote areas. On an average, the ratio of nurses per 1,000 people is well above the WHO standard of 2.5 nurses per 1000 people in Australia, i.e. there were 12 nurses per 1000 people.270 Thus, regardless of the fact that metropolitan regions in Australia do not face shortages, certain regional areas in states like Victoria and South Australia are facing skill shortages for nursing staff and are unable to fill vacancies.

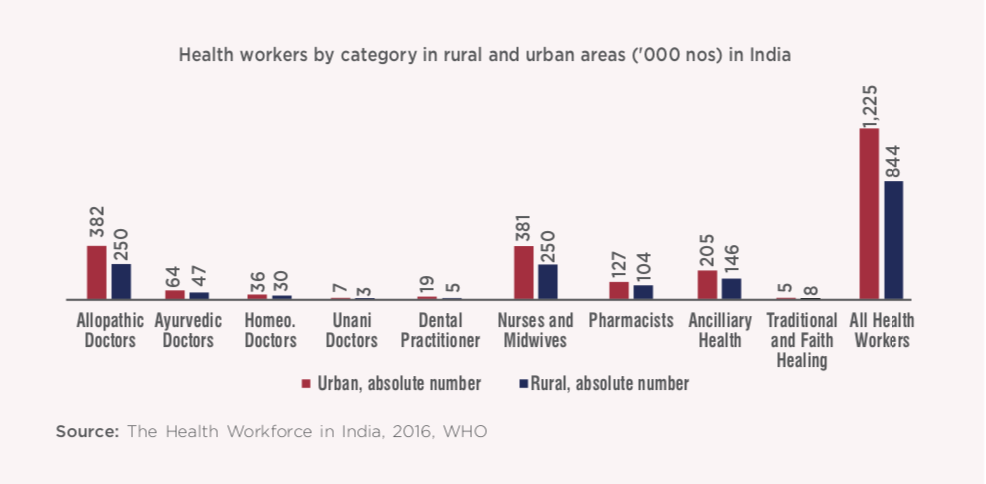

The health workforce in India comprises of broadly eight categories, namely: doctors (allopathic, alternative medicine); nursing and midwifery professionals; public health professionals (medical, non-medical); pharmacists; dentists; paramedical workers (allied health professionals); grass-root workers (frontline workers); and support staff.271 While this sector in India employs 5 million people, the density of healthcare professionals is extremely low. India also faces issues such as acute shortages and inequitable distribution of health professionals.271 Medical facilities are heavily concentrated in urban regions, while in rural regions they are under-developed. For example, Maharashtra has ~154,000 registered doctors, compared to just 792 registered doctors in Arunachal Pradesh.272 Medical workforce requirement in India is expected to further grow from 3.6 million in 2013 to 7.4 million by 2022.273

Public health insurance

Medicare Australia

Australia provides universal healthcare to its citizens through its universal health insurance scheme – Medicare. It guarantees all Australian citizens and permanent residents, access to a wide range of health and hospital services at low/ no cost. Apart from the general taxation revenue, Medicare is funded by 2% Medicare levy charged over and above federal income tax rates.274 Medicare cardholders have access to free-of-cost treatment in public hospitals. Medicare cardholders can also purchase prescription medicines at a subsidized cost under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. However, certain medical services such as ambulance services, dental examinations and allied health services such as physiotherapy and optical aids (such as glasses and contact lenses) are not subsidized under Medicare.

Ayushman Bharat Scheme

In India, expenditure on healthcare is largely borne by individuals from their own pocket. Of the total health expenditure, only one third is borne by the public sector. This contribution is far lower than countries such as Brazil (46%) and China (56%).275

The Ayushman Bharat Scheme or the Pradhan Mantri-Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) is one of the Indian Government’s largest initiatives to structure the healthcare sector in the country. It aims to integrate latest technology and synchronize between various healthcare value chains such as state agencies, insurance firms and trusts, third party administrators and public and private hospitals. As a part of this initiative, the Government has envisioned to open 0.15 million health and wellness centres as comprehensive primary health care centres (PHCs) that will provide maternal and child health services, mental health services, vaccinations against select communicable diseases and screening services for hypertension, diabetes and select cancers.276 This scheme also sets out to provide essential medicines and diagnostic services free of cost to its patients.

The Government has also introduced the National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS), which will provide a cover of up to Rs. 5 lakhs (USD 714.3 million) per family per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalization. The NHPS is the largest funded public insurance scheme in the world that is expected to cover 100 million poor and vulnerable families and have 500 million beneficiaries covering around 37% of the population.277 Hence, NHPS is the first step taken by the Government to introduce universal health care in India.

Opportunities for collaboration

The following opportunities for collaboration in the healthcare sector exist in the private and public domain. The areas of collaboration pertaining to B2B collaborations with in the private sector can be under taken through various forums and organizational summits such as the Australia-India Business Forum, etc.The areas of cooperation and collaboration within the public sector continue to be discussed in the Joint Working Group (JWG) for Health Cooperation formed by both countries.

1. Healthcare Governance

Primary health care represents ‘Level One’ of the healthcare system of any country. Efficiency of primary healthcare is the first step towards ensuring improved health standards and reduced costs. The healthcare set up of a developed economy is usually characterized by a robust primary healthcare establishment. Accordingly, the primary healthcare scenario in Australia is largely reflective of the sector in other developed countries such as the UK and Canada. Primary health networks (PHN) have acted as the backbone of the health care system in Australia. They have enhanced the quality of healthcare amenities by ensuring seamless integration and exchange of information of patients’ backgrounds and medical histories with the concerned health professionals at each successive level.

In theory, India has a well-defined healthcare system, where preliminary health problems are expected to be treated by identified Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) that are then required to screen and transfer more serious cases to specialist hospitals in districts and further to state-level hospitals. However, in practice, most PHCs are plagued by poor infrastructure and staff availability challenges. There is also a significant disparity in provision as well as quality of primary healthcare services in urban and rural India. Problems with early detection and prevention of illnesses, a pre-requisite to reduce the disease burden in the country, also emanate from poor access to primary healthcare. Furthermore, primary healthcare providers are largely fragmented in the country and lack alignment with healthcare vendors at secondary and tertiary levels.

The Ayushman Bharat Scheme has the objective to redesign the primary health network in India. The lowest level healthcare facilities, that currently provide selective care, are being converted to Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) to provide all-inclusive primary treatments. The Indian Government has a target to revamp ~1.5 lakh sub- centres to HWCs by 2022.271 In addition, State Governments are also expected to develop their own roll out plans and prototypes to suit their respective state environments. For example, the Kerala Government has decided to provide comprehensive services at the primary health level itself rather than converting sub-centres.

Ayushman Bharat is the Indian Government’s most ambitious healthcare reform plan till date. At this stage, professional expertise and management of healthcare utilities is the need of the hour. Australian expertise in modelling healthcare systems and organizing rural health amenities will be beneficial in tackling India’s healthcare challenges. Discussions between both countries in this space had been initiated in 2014, such as the talks between officials of the Australian Department of Health with the Ministry of Health and All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in India to identify potential areas of cooperation in healthcare. Further discussions between Governments, stakeholders and leaders in the healthcare sectors in both countries should be facilitated and expedited to streamline India’s healthcare at the grassroots level.

Sector Representative Contribution: Healthdirect

Healthdirect Australia is a national, government-owned, not-for-profit organisation providing free health information advice and information to Australians via telehealth services, including helplines, video call, websites, service finders, mobile applications and social media networks.

Core services

Telephony and digital services aim to connect people with the right part of the health system, so they receive the right care at the right time. This is particularly important for people needing medical help in the after-hours period or if they are unsure about which course of action to take.

healthdirect provides 24/7 access to health information and advice via a range of digital channels and a telephone helpline to help people make more informed health decisions. It is a free national service delivered across a variety of channels – phone line, website, app, voice apps. There is also an after- hours GP helpline which is an extension of the healthdirect helpline and is operational at night, on weekends and during public holidays. This health- grade technology provides a platform to healthcare providers to offer their services directly to patients via video consultation and integrate telehealth as an everyday part of a modern Australian health system.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is a national service that provides support and information for parents, families and carers on the journey from pregnancy to pre-school either online, over the phone, via video call and social media.

The National Health Services Directory (NHSD) is a comprehensive, up-to-date and accurate online directory of Australian health services and the practitioners . It is a key piece of national digital health infrastructure.

In addition, healthdirect also provides other services such as free and confidential motivational coaching, lifestyle coaching, etc.

This platform could be adopted in India, in line with the Indian Government’s digital health initiatives

Further, Australia’s National Digital Health Strategy has implemented various successful Digital Health Initiatives such as My Health Record. It has also led the foundation of Global Digital Health Partnership (GDHP), which is the largest inter-governmental platform and includes 30 WHO member countries. Australia served as the inaugural Chair of GDHP. In February 2019, India was elected as the Chair of the GDHP and Australia is supporting the GDHP as Co-chair. This partnership can provide economic opportunities for IT and ITES organizations in India to leverage benefits on the digital health platform focusing on provision of health IT services (as Health Solution partner, implementation partner, consultancy provider and partner for disruptive Technologies (AI, Big Data, IoTS) etc.) both on-shore and off-shore to global clients.

2. Medical Coding and Data Analytics

The International Classification of Disease (ICD) is a standard diagnostic tool implemented by the World Health Organisation (WHO), which is a code system for classification of diseases. The ICD has varied applications and is used by doctors, paramedic staff, insurance companies, researchers and policy makers.

Clinical coding has been performed for over 60 years in Australian hospitals for health service management, planning, activity monitoring and epidemiological studies. It is usually the first stage in medical billing. Medical coders ensure that codes (in accordance with relevant standards) are applied correctly during the billing cycle and the process includes extracting data from documents, assigning appropriate codes and creating claims for insurance companies. Clinical coding requires an extensive knowledge of medical terminology along with an analytical ability to translate medical records into appropriate codes.

India’s strengths in information technology, driven by a large and skilled workforce, has resulted in India emerging as a popular outsourcing destination for medical coding. Approximately 80% of the US companies outsource their medical coding operations to India.278 Indian medical coders are well-equipped to deliver customer- centric solutions that can be utilized to cater to the requirement of various types of organizations (i.e. hospitals, clinics, academic medical centres, etc.) in Australia.

Apart from medical coding, in recent years, the requirement for big data analytics has grown manifold owing to deep insights that can be obtained to improve healthcare services and patient outcomes. Data analytics has quickly moved from being restricted to IT and finance to other sectors such as healthcare. Data mining and analytics, derived from medical databases, is an emerging trend in the healthcare sector. It is required by healthcare providers and insurance companies alike. Data analytics in healthcare finds applications in multiple areas that include public health analysis, patient profile analytics, fraud analysis and safety monitoring.279 A sound medical coding mechanism, coupled with domain knowledge and robust IT skill availability in India implies that India can further leverage its expertise in the sector to work towards this new and upcoming trend for Australian healthcare companies.

Data on health in India is plagued by insufficient inputs that severely affect policy planning in the country. There are also issues with consistency, comparability and usability of data at a national level. Medical coding, if carried out accurately, has several benefits. It results in procedural efficiencies and promotes transparency and ease in data collection. It also standardizes the billing process in addition to environmental advantages of making the industry paperless. While India has established itself as a hub for outsourcing of these services, medical coding and medical data collation in India itself is at a nascent stage. Unlike developed countries, medical coding in India is not strictly implemented or required by hospitals and insurance companies. The use of ICD-10 has been very recent with its implementation in only 11-12 Indian hospitals.280 Medical coding in India may further improve the current discordance at multiple points of data collection in the country.

Sector Representative Contribution: Synapse

Synapse Medical Services is a leading international provider of medical administration services with over 30 years’ experience in the international healthcare sector. Synapse’s services include cutting edge technology, clinical coding and billing, health system classification, consulting and health administration education. Synapse, founded by Margaret Faux in 2009, began as a modest medical billing service solely in Australia, serving individual practitioners, clinics and hospitals. In 2015, Synapse established an office in the southern Indian city of Chennai and now employs 130 people in its wholly owned Indian office. Additionally, the Synapse group now also has an office in the Middle East and the three offices combine technology and resources across different time zones to work in tandem seamlessly. Synapse provides administrative support for clinical services in Australia, with an integrated delivery centre for medical billing, clinical coding and transcriptions in India. The key focus areas include using technology to decrease paperwork for healthcare professionals, so they can focus on frontline service delivery and patient care. In 2018, Synapse also became a Registered Training Organisation under Australia’s vocational education framework and the non-clinical courses it now offers target modern, progressive medical administrators and managers to improve health system literacy across the globe.

At Synapse, the India and Australian offices are viewed as one. They use time differences to their advantage, processing work around the clock. They move staff between their Sydney and India offices constantly and their Sydney based managers visit the Chennai office frequently. The Australian staff work at the customer interface while Synapse India works at the data interface. Having a service centre in India has augmented Synapse’s capacity and capability that has led to winning new contracts in other countries including India.

India is paramount to the long-term plans of the company as it houses their main delivery centre and has the highest number of staff. Additionally, since India has committed to Universal Health Coverage and the introduction of Ayushman Bharat, Synapse is engaged with key stakeholders in India’s health system journey, discussing both education and up skilling the local population and also providing health system services and software solutions.

3. Hospital Governance – Trauma Care

Trauma care entails immediate treatment to critically injured patients in the aftermath of a natural/manmade disaster, accident, etc. The first hour of treatment after a serious injury is crucial and the right medical treatment in that duration, when the chances of survival and minimum disability are the highest, is essential. In India, road accidents are the leading causes of disability and mortality. With the number of vehicles on Indian roads on the rise, the exposure to road injuries and deaths has also increased. India accounts for 6% of the world’s total road accidents with merely 1% of the world’s vehicles.281 In 2016, at least 17 deaths occurred from road traffic accidents every hour. Road accidents also result in precious loss of demographic dividend and in 2016, the working age group of 18-60 years accounted for ~83% of the total road accident fatalities.282 Road traffic death statistics in high income countries have witnessed a downward trend or have largely stabilized. However, in countries such as India, road accidents have been on the rise. While these statistics are alarming, the overall number of casualties can be significantly reduced with adequate trauma care. More than half of the cerebral injuries that occur as a consequence of road accidents can be remedied with appropriate pre-hospital trauma care systems.

Currently, India does not have enough hospitals/clinics with adequate trauma care. Furthermore, the unavailability of adequate infrastructure makes it extremely difficult for ambulances to reach patients and hospitals promptly. The integration of resources at the pre-hospital environment, at the hospital where primary treatment is administered and at the tertiary level is required for the time-critical trauma care system to be effective.

The Indian Government has taken initiatives to address this with schemes such as, “Capacity Building for developing trauma care facilities on National Highways” that includes setting up trauma care facilities along national highways at every 100 km and includes training courses for doctors, nurses and paramedics.283 However, trauma care in India is still at a formative stage. There is also sufficient disparity in the availability of facilities between rural and urban areas.

4. Training of healthcare workforce

India has a considerable requirement for an adequately trained and skilled medical workforce. With a population that grows at a rate of ~26 million persons ever year, India has merely 462 medical colleges that train ~57,000 doctors and 3,000 institutions that prepare ~126,000 nurses annually.272 Further, healthcare service delivery is now not only the prerogative of doctors and nurses, but also vastly dependent on the services of allied health staff, also known as ‘paramedics’ or health technicians. The medical industry in India thus requires stringent quality frameworks that can standardize training processes for different vendors in the healthcare value chain. With technology driving future trends in the sector, along with a shift in requirement to 24 hours, 365 days a year facilities and the Indian Government’s efforts towards making universal health coverage a norm, the need for well-qualified, well trained medical staff is indispensable. This could entail providing training for basic services such as sample collection, early diagnostics, basic health check-ups, elaborate patient management, medicine administration, etc. Shortage of doctors and inequitable distribution of medical staff results in a large part of the healthcare demand in rural areas being addressed by informal workers.

The Union Health Ministry in India is also encouraging and taking steps to standardize the medical staff training process in the country. In 2019, NITI Aayog organized talks on nursing education reforms with experts in the industry. The importance of integrating IT in the training curriculum was also discussed.

In Australia, the healthcare and social assistance industry is a training intensive industry where over 76% of the workforce has a post-school bachelors degree or have undergone vocational training.284 India can thus collaborate with Australia for healthcare education and training. Training could be imparted by joint medical courses and certificate courses by Indian and Australian institutes. Australian institutes can also impart online training to Indian healthcare personnel. There is also an opportunity for medical community exchange programs, where trainers and workforce personnel from rural India visit regional Australia to share best practices, while regional Australian students can work in Indian communities as part of their healthcare training. India and Australia can also collaborate on tribal and rural health training.

5. Aged Care

Ageing is a global issue. The world’s population is getting older due to increasing life expectancies and decreasing birth rates. India has not been spared from this demographic transition and the country’s aged population is rising rapidly. India is expected to have more than 340 million people over the age of 60 years by 2050.285 The leap in the numbers of the country’s grey-haired population presents significant challenges to India’s healthcare system. While keeping senior family members under care in assisted living centres or old age homes has been historically accompanied by societal judgments and social stigma in India, the concept is slowly gaining acceptance in the country. Urbanization is on the rise and the traditional joint family system in the country is slowly disintegrating. A wave of migration in recent years that has resulted in many young Indians moving abroad and the large number of women in the workforce are glaring reminders of the need to prepare adequately for geriatric care in the country. This issue is particularly more pronounced for senior citizens who require a higher level of care from serious illnesses that their immediate families cannot provide.

The Indian Government has made some interventions to tackle this issue. For example, in 2007 the Indian Government passed the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, which requires children to take care of their elderly parents. The Government also introduced the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE), However, the impact and reach of these measures on geriatric care in the country is debatable. As of mid-2017, only 360 old age homes had been set up with Central Government assistance.286 India’s private sector has made some inroads in this segment, with as many as 30 assisted living projects and another 30 under development. There are also several real estate developers venturing into setting up retirement facilities with state-of-the-art amenities across the country. However, these facilities are expensive and largely cater to the highly affluent segment. The mid-tier, affordable segment in this space is dominated by non-profit organizations and private organizations. However, in the old age homes run by these organizations too, the number of beds is significantly outweighed by their requirement. These homes are also significantly understaffed. There is a dearth of adequately trained geriatric healthcare professionals in the country. The lack of Government-imposed industry standards also poses questions of quality and standardization.

The ageing of the population and the associated increasing number of people with dementia are the two main factors driving increased demand for aged care services in Australia. By 2050, over 1.8 million Australians are expected to be above the age of 85, with an estimated 3.5 million expected to need access to aged healthcare services. The Australian Government has been highly involved in providing geriatric care. In addition to the Government, aged care in Australia is offered by non-profit organizations and private organizations. ‘My Aged Care’ is the Government subsidized support offered to Australian citizens. The aged care system offers three different types of services – Commonwealth Home Support to support individuals to undertake everyday tasks on need-basis requirement, home care packages depending on the level of medical need and residential care to provide accommodation for people requiring higher levels of care. The home care package offers supplementary support such as cleaning, shopping services, home visits by nurses and equipment to help with mobility, etc.

India needs to upgrade its geriatric healthcare system. One of the key areas for collaboration with Australia can be for training and skill development. Australian aged care bodies can assist Indian organizations with training materials, mentoring and resources required to enhance skills in this sector. The private sector in India has been trying to plug the demand supply gap with senior living and assisted living projects. Indian private organizations can collaborate with Australian companies in this sector by forming joint ventures.

6. Opportunities for Australian investments in the Aged Care Segment in India

Several Indian companies such as India Home Health Care, Portea Medical, Epoch Eldercare etc. are seeking to expand investments in the aged care industry. Rising demand for geriatric care in the country is expected to create significant opportunities in products such as power wheelchairs, home monitoring BP devices, wearable devices to record patient vitals etc., retirement communities and specialized staff that include physiotherapists, medical suppliers, etc. Indian private sector players have displayed a keen interest in investing in this sector.Australian investors should also be encouraged to tap into India’s growing geriatric healthcare market.

7. Medical devices

Australia’s medical devices are globally recognized for their innovation. Australia’s medical technology sector comprises over 500 companies and has established a global reputation and track record for being innovative, especially in areas such as bionics and implants. Companies such as Cochlear Ltd, Cook Medical Australia and ResMed are some renowned companies in this space. The sector generates a revenue of AUD 11.8 billion (USD 7.9 billion). Most businesses in this sector are SMEs (54%) that have grown from start-ups, though Australia also has a sizeable number of large multinationals in this space (35% of businesses).287 The industry has several inventions to its credit such as 3D customized titanium implants, non-invasive blood glucose monitoring systems, long-wearing night and day contact lenses, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices for sleep apnoea, etc.287

In an effort to reduce dependence on imports, the Government of India has sanctioned the setting up of 8 manufacturing parks, 4 each for bulk drugs and medical devices.288 The idea is to have Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) build the necessary infrastructure and receive clearances in place for these parks.

This presents an opportunity for Indian health care companies to invest in Australian start-ups that have unique medical device technologies. The scale of manufacturing can be supported in India to commercialize device technology developed by Australian SMEs. In the long run, this can help develop a thriving medical technology segment in India. Indian companies can leverage the reputation of Australian device companies to access developed markets. Australian companies can also utilize and leverage India’s strengths in low cost manufacturing and to reduce costs and increase margins.

8. Medical Technologies

The Indian med-tech market, valued at ~USD 10 billion, is expected to grow at a CAGR of 15-20% by 2025.289 While the domestic market is still nascent, the Indian Healthcare Information and Communications Technology (ICT) market is forecasted to grow 1.5 times by 2020. The growth in this market is expected to be driven by digital health start-ups.290

The digital health start-ups in India are introducing new technologies such as wearable-tech, telemedicine, genomics and artificial intelligence to the Indian healthcare system that are trying to drive demand towards ICT-led delivery and consumption of healthcare services.

The Government of India has initiated the following policies to realize the full potential of the sector:

- Allowing 100% FDI in developing the quality of medical devices and infrastructure facilities.

- The set-up of bio incubators and technology entrepreneurship parks, such as the Andhra Pradesh MedTech zone, InnAccel Bangalore and IKP-EDEN are expected to reduce import dependency and offer resources for product development.

The latest trends in the field include the following:

- Management information systems for consolidating and holding healthcare related data

- Electronic medical records

- Telemedicine in rural areas

- Computer aided diagnosis for assisting radiologists; robotics and non-invasive treatments.291

Moreover, the products in this sector are focusing on arriving at clinical solutions, in addition to their offerings in administrative challenges. A few Indian start-ups in this sector include:

- Practo, initially only offering a SaaS based clinical management software to doctors, has developed online consultation, medicine delivery and patient management software.

- Healthifyme is an application, which is designed to collect health data to recommend personalized exercising and diet plans.

- Qure.ai provides AI solutions for efficient diagnosis. It uses the database on radiology images to detect abnormal X-Rays and imaging scans.

- 99Dots focuses on cost-effectively diagnosing tuberculosis in patients.

- Online pharmacies, such as 1MG, Myra and Netmeds have also gained popularity in India.

Australian strength in medical innovation can thus be harnessed by the Indian healthcare system to support the country’s growing economy. Medical technology is a growing market in India and Indian start-ups in this space can leverage the established framework of Australia’s medical technology market to develop similar technologies in the country. India’s growing capabilities in IT, data analytics, IoT driven solutions, AI and SaaS solutions can be leveraged by Australian med-tech start-ups in their pursuit of arriving at cost-effective solutions in this space.

Additionally, Australian medical technology start-ups can widen their scope of commercialization by tapping into the Indian market. This opportunity will enable Australian med-tech start-ups to not only access a wider market but also establish the brand value of their innovations at a faster pace.

Further, India and Australia have entered into collaborations across the medical technology space over the last three years. A few examples of these are as below:

- Andhra Pradesh Med Tech Zone (AMTZ), Vishakhapatnam and the University of Wollongong have signed an MoU for 3D printing of medical devices. While the Australian university will provide expertise on the usage of bio-inks, AMTZ will offer one of the largest 3D printing facilities in the world. A series of knowledge programs such as ‘AusInnovex’ have been conducted jointly under this partnership.

- Flinders Biomedical Enterprises Pty Ltd (FBE) based out of Adelaide specializes in repair of endoscopes which is a highly rated skill and has set up a subsidiary in India. Further efforts are being directed towards setting up the Australian India Centre of Excellence for Endoscopes.

- George Institute of Global Health in Sydney is collaborating with start-ups in the medical technology space for integration of start-ups in early value chain of Indian medical devices sector.

Opportunities for Australian investments in the med tech sector in India

India’s digital healthcare is an attractive domain for several investors. India has around 2,975 med-tech startups that belong to various categories across the healthcare value chain i.e. home healthcare, diagnostics, pharmacies etc. Furthermore, as per Invest India, the medical devices industry is expected to grow at 28% to reach USD 50 billion by 2025. In 2015, the Indian government allowed 100% FDI in medical devices under the automatic route to encourage foreign investments in this sector. This sector thus presents significant opportunities for attractive returns to Australian investors.

9. Expert Consultations

Second opinions, especially in diagnosis of crucial illnesses, have become indispensable to reduce healthcare charges and to minimize clinical errors. A study conducted by the Mayo Clinic found that ~88% patients, who sought a second opinion received a new diagnosis after the second round of consultation292. Furthermore, 10-15% of illnesses are misdiagnosed, resulting in additional costs of USD 15 billion from irrational use of medicine and medical procedures293. Thus, while second opinions are being encouraged, expensive medical bills in developed countries means that most people shy away from getting additional specialist opinions. While most of Australia’s citizens are insured under Medicare or private health insurance, they still incur a large out-of-pocket fees for specialist opinions because the cost of a second medical opinion is dependent on the doctors’ charges and the rebate Australian citizens receive from Medicare, which can vary significantly.

Digital engagement in healthcare has resulted in a paradigm shift in the way doctors are being consulted and illnesses are being diagnosed. India has several start-ups that offer a medical platform for foreign patients seeking second opinions. These start-ups allow the online exchange of medical files and treatment plans without the need of a physical visit. For instance, TreatGo is a Kochi-based start-up that is seeking to expand its scope of offering second medical opinions by offering treatment options at leading Indian hospitals. Indian doctors can also provide second opinions or expert consultation on medical reports to Australian patients at highly discounted rates as compared to other Western countries. While these expert opinions are discounted, they are as insightful as the ones offered by the doctors in Australia. Therefore, Australian patients can use the cost-effective advantage and quality of expertise offered by Indian doctors to receive a second opinion on their medical diagnosis.

10. Cancer Research

Cancer poses a strong challenge to economic and social progress around the world. Countries need to not only take a customized local approach but also collaborate with other countries to collectively address and overcome the risk of cancer.

Cancer is a significant cause of illness in Australia affecting over 1 million people in the country, who are either currently battling or have survived cancer.294 Cancer is further expected to affect approximately 150,000 people in Australia by 2020.294 The five most common types of cancers in Australia include lung, breast, prostate, colorectal and melanoma cancer.295

In light of the current and projected impact of cancer, the Cancer Australia Strategic Plan 2014-2019 was developed by Cancer Australia and the Government of Australia. The vision of the plan was to mitigate the effects of cancer and improve the well-being of those affected. This plan is responsible for Australia’s first national database for the stage, treatment and recurrence of cancer. Australia has one of the best survival rates for all types of cancer in the world. Australia has three population- based screening programs for breast, bowel and cervical cancer. These screening programs are offered free to all Australians. In addition to these programs, the Government also offers subsidized monitoring and detection tests under Medicare. These programs have contributed to the increase in Australia’s current five-year survival rate, which has recently increased to 68%.296 The Australian Government is the largest investor in cancer research in Australia and in the past four years, the Australian Government has invested over AUD 10 billion (USD 7.14 billion) to fight and control cancer.297

Cancer patients in Australia also have access to new treatments on account of AUD 5.1 million (USD 3.4 million) research partnership between CSIRO and GenesisCare, one of Australia’s largest cancer care providers.298 This partnership aims to bring new targeted therapies for patients suffering from the most fatal kind of cancers, such as brain, pancreatic, ovarian and metastic cancer.299

Cancer is a major cause of concern in India as well and the number of cancer cases is progressively increasing every year. In 2016, India had 14 million patients suffering from cancer and this number is on the rise.300 The most common types of cancers in India include breast, oral, cervical, gastric, colorectal and lung cancer. However, early prevention and detection can significantly improve survival rates in India.

Preventive approaches towards cancer have been initiated in India. For example, the National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research has been instrumental in creating an operational framework with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare for the management of population- based cancer screening in 100 districts of India.301 However, these initiatives have not been implemented at the grassroots level. For instance, less than 30% of women in India undergo screening tests for cervical cancer. While the issue of cervical cancer is pressing, given that the disease contributes to over 60,000 deaths, there is low participation amongst patients due to the lack of awareness and limited access to screening and treatment services in India.302

In the last few years, India has made significant progress in cancer research and has several international collaborations to its credit in this field. In the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, several reforms were announced by India’s Finance Minister to revive the Indian economy in mid-May 2020. It was announced that reforms within the field of atomic energy for the production of medical isotopes for affordable treatment of cancer will be undertaken by the Central Government of India. India has become an active member of the International Agency for Cancer Research. India also serves as an important center for training and education in epidemiology for WHO’s Southeast Asia region. India hosts the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s regional hub for cancer registration, which is one of the most important initiatives in leading cancer epidemiology and secondary research in developing countries worldwide.303

While there have been successful partnerships in the field of research with other countries, India can forge new partnerships with Australia to adopt successful models of early detection and control programs. These programs can vastly improve India’s survival rates of cancer. While initiatives have been taken by the Government of India, India can collaborate with Australia to learn from its outreach programs in raising health awareness and increasing active participation amongst citizens in screening programs.

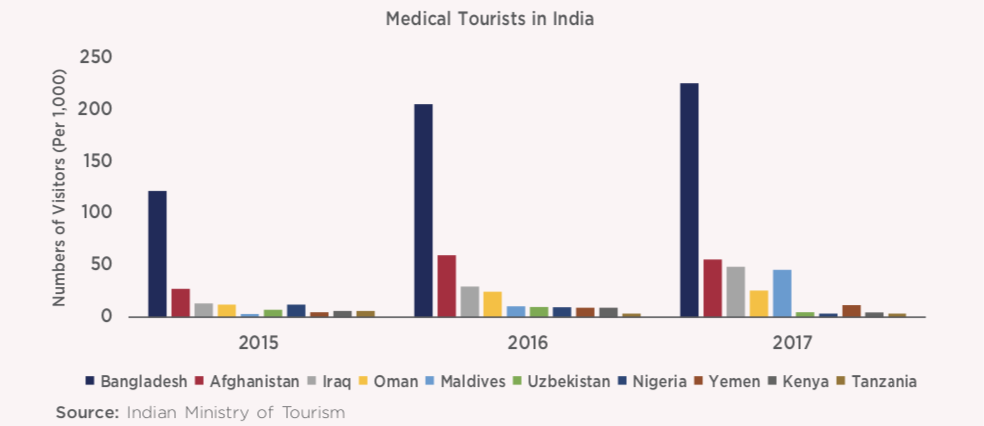

11. Medical Tourism

While the primary healthcare scenario in India needs vast improvements, the country has an advanced tertiary care sector, especially in urban pockets. Advanced facilities, highly skilled doctors and advantageous price differentials in medical treatments have attracted several medical tourists to India. India has large hospital chains that offer state of the art tertiary treatments. For example, the Apollo Hospital Group has multi- speciality hospitals and satellite chains set up across the country and outside India that are known for specialized treatments in cardiology, hip-replacement and neurology; Max Healthcare has a growing international clientele due to internationally renowned cardiology treatments and use of up-to date modern technology; Tata Memorial Centre is globally ranked as one of the top hospitals for oncology. Medical tourism is one of India’s major sources of foreign exchange. The medical tourism industry was valued at USD 3 billion in the year 2015 and is projected to be valued at USD 8 billion, accounting for 20% of the global market share by 2020.304

Apart from tertiary care, cosmetic surgeries and dental procedures are highly affordable in India. Medical procedures in Australia such as a hip replacement on an average, costs two-three times (USD 13,850- USD 27,700) more than the amount in India (USD 9,000). ~15,000 Australians travel overseas for medical treatment each year.305 With rising insurance premiums, even basic hospital insurance becomes unaffordable for many Australians and therefore supplemental extras such as dental care are preferred to be carried out overseas.306 The most popular treatments amongst Australian medical travelers include facelifts, spinal surgeries, neck surgery, hip replacements, knee replacements, shoulder reconstructions and fertility treatments.

While India witnesses an influx of patients from Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Iraq, Maldives, Oman, Yemen, Uzbekistan, Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania, the share of patients from Australia is relatively less.

This could be on account of the lack of direct flights and lack of awareness about medical procedures in India. In order to further incentivize the medical tourism industry and encourage travel from Australian citizens, the Government of India should extend its support by improving infrastructure to ensure a comfortable stay for foreign visitors. India needs to develop a one- stop service that will provide travel, lodging, cashless direct billing, efficient customer service and post-hospital care coordinated via a single portal or call centers to its medical tourists. Nasscom companies could provide the industry with the necessary technology and business transformation know-how to make this whole process smoother. Large companies such as Tata, Fortis, Max, Wockhardt and Apollo Hospitals have already made significant investments in the establishment of modern hospitals and tourist services to host international patients. These companies can also partner with Australian private health insurance companies to provide attractive health travel packages that ensures Australian travelers large cost savings. Such a partnership, in turn, will raise confidence in and awareness about India’s healthcare system. The Joint Commission International, a non-profit organization based out of the US, is an independent global accreditation agency that evaluates, classifies and offers innovative solutions to health care organizations across the world. A similar set-up agency in Australia can also provide an additional safety measure to Australian citizens travelling to India, while also incentivizing Indian hospitals to raise their standards.

Recommendations

- To promote Indian medical tourism in Australia, the Indian Government should establish a medical tourism framework with support infrastructure to ensure a comfortable stay for Australian visitors who come to India for procedures such as dental care, major and minor cosmetic surgeries, etc.

- Large private hospitals, in collaboration with the Indian Ministry of Tourism, need to develop a one-stop service that will provide travel, lodging, cashless direct billing, efficient customer service and post-hospital care for Australian medical tourists. Nasscom companies could provide the necessary technologies to make this process smoother.

- Indian companies could explore partnering with Australian med-tech start-ups and supporting them with funding requirements for large scale commercialization to target the global market. This could be done by way of signing MoUs between Indian and Australian companies as well as setting up Med-tech parks.

- Indian Government should engage with Australian aged care companies to encourage investments into building an aged care ecosystem in India.

- Australian investments should be encouraged by India in the primary healthcare, e - health care areas

258 The United States Health System Falls Short, The Commonwealth Fund, 2017

259 Australia Health, 2018; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare, Australian Government, 2018

260 Tackling doctor’s shortage, The Pioneer

261 Primary Health Networks, Health direct 262- Australia’s hospitals 2016-17 at a glance, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

263 Non-communicable diseases cause 61% of deaths in India: WHO report, Times of India, 2017

264 Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

265 Branded Pharmacy chains pump up the volume, Business Standard

266 Retail Pharmacy Market Scenario of India, Hospaccx 267- Australia’s other great duopoly is literally pathological – Sonic and Primary, Sydney Morning Herald

268 Pathology of regulation, 2018, Business Today

269 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australian Government

270 Nurses and Midwives (per 1,000 people), World Bank Data Bank

271 India facing critical shortage of healthcare providers: WHO, The Hindu 272- India’s public health system in crisis: Too many patients, not enough doctors, 2017, Hindustan Times

273 India’s healthcare sector to require 74 lakh employees by 2022: NSDC, 2015, The Economic Times

274 Australian Government, Australian Taxation Office, Medicare Levy

275 Healthcare financing: Who pays for healthcare in India? 2018, Moneycontrol

276 1.5 lakh wellness centres to be set up under Ayushman Bharat: MoS for Health Ashwini Kumar Choubey, 2018,The Economic Times

277 Ayushman Bharat health insurance: Who all it covers, how to apply, 2018, The Economic Times

278 Opportunities galore in medical coding, 2017, Deccan Herald

279 Data security and Analytics, Asian Hospital and Healthcare Management

280 Indian Journal of Public Health, 2015, Implementation of ICD 10: A study on the doctors’ knowledge and coding practices in Delhi

281 Rs 554 crore national trauma care policy awaits cabinet approval, 2017, Live Mint

282 Post-crash care in India, JPN Apex Trauma Center

283 Trauma Care Centres for Road Accident Victims, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, 2019

284 Australian Jobs 2018; Department Jobs and Small Business, Australia 285- Demographic time bomb: Young India ageing much faster than expected, 2018, The Economic Times

286 Here’s what the future of the senior living industry looks like for 25% of India’s population, 2018, Business Insider

287 Medical Devices and Diagnostics, Australian Government, 2016

288 Manufacturing hubs of medical devices, bulk drugs in offing, 2019, Business Standard

289 Purposeful innovation: How start-ups are solving challenges plaguing Indian healthcare, The Economic Times

290 Digital health start-ups in India: The challenge of scale, Forbes India

291 Emerging Trends in Medical Technology, Elets Technomedia Pvt Ltd

292 The value of second opinions demonstrated in study, 2017, Science Daily

293 Irrational Uses of Medicines – A Summary of Key Concepts, NCBI

294 Cancer in Australia, 2019, Australia Institute of Health and Welfare

295 Cancer Council Organization of Australia

296 Cancer incidence, mortality and survival in Australia, Australian Government, Cancer Research

297 Cancer Australian Government, Department of Health

298 New $5m research project to treat ‘untreatable’ cancers, 2019, CSIRO 299- Working to treat ‘untreatable’ cancers, CSIRO, 2019

299 Working to treat ‘untreatable’ cancers, CSIRO, 2019

300 Indian Medical Research Center, 2016

301 ICMR – National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research, National Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research

302 Fewer Women undergo test for cervical cancer despite Government push, Live Mint

303 Cancer Burden and Health systems in India, Tata Memorial Center

304 Indian medical tourism industry to touch $8 billion by 2020: The Economic Times

305 Medical Tourism and Insurance, Better Health – Victorian Government 306- Medical Tourism: 500,000+ Aussies Heading Overseas For Procedures In 2017, Canstar

Next topic: