Focus Sectors

Agribusiness

Synopsis

Australia has an abundance of natural resources and is recognized internationally for the productivity of its agriculture sector and its high quality exports. Scientific advances have helped Australian farmers put themselves at the forefront of efficient and productive agricultural practices in the world.

India is the leading producer of several commodities such as rice and wheat. The Indian agribusiness sector has significant untapped potential that could be enhanced with access to Australian technologies that improve both yield and quality of agri-farming and output.

The following opportunities have been identified for this sector:

- Increasing knowledge transfer initiatives between India and Australia in agri-technologies

- Adopting best practices in dairy processing

- Collaborating with Australian Government/ companies for innovative storage techniques

- Investing in farm lands and wool farms in Australia

- Collaborating with Australian companies in areas such as aquaculture and deep-sea fishing

- Investing in Australian food processing

- Exporting India’s Ready to Eat products to Australia

- Encouraging research partnerships with Australia to develop India’s biofuel potential

- Promoting investments by Australian companies in India’s mega food parks

Macroeconomic Overview – Agribusiness in Australia

The agricultural sector in Australia is renowned for its high productivity, technological advancement, innovation and high quality of produce.307 This sector, which employs more than 300,000 people, is one of the strongest pillars on which the Australian economy is built. About half of the land area in Australia is utilized for agricultural activities. It is one of the fastest growing sectors in the economy, contributing 2.6% (~USD 30 billion) towards the Australian GVA.308 Australia is on par with other developed nations like France, the US and the UK in terms of the share of agriculture (1-2%) in the overall economy.

Agricultural production in Australia

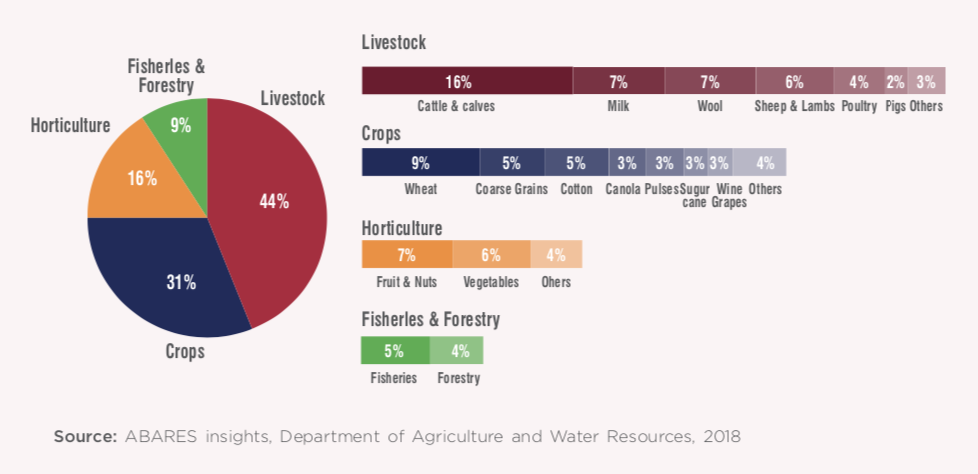

Agricultural production in Australia can be categorized into four broad categories: livestock (44%), crops (31%), horticulture (16%) and fisheries and forestry (9%).

Livestock includes animal rearing for consumption of meat as well as products such as wool, dairy, etc. It is the fastest growing category in the agriculture sector in Australia and livestock production has grown by more than 50% over the last 20 years. Specifically, the rearing of cattle and calves (for beef) is the largest activity within livestock farming, contributing 16% to the overall livestock output.309 Australia is amongst the top ten dairy producers in the world with the highest value addition domestically. Crop cultivation is the second largest activity under agriculture and comprises of cultivation of grains like wheat and other coarse grains such as barley, oats, etc. and crops like sugarcane and oilseeds. Australia is amongst the top ten wheat producers of the world producing 35 million tons in FY 2017-18.310 Horticulture is the third largest category within agriculture comprising of cultivation of fruits and nuts worth ~AUD 4.9 billion (USD 3.3 billion) and vegetables ~AUD 4.1 billion (USD 2.8 billion).309

Regional map of Australia’s agriculture

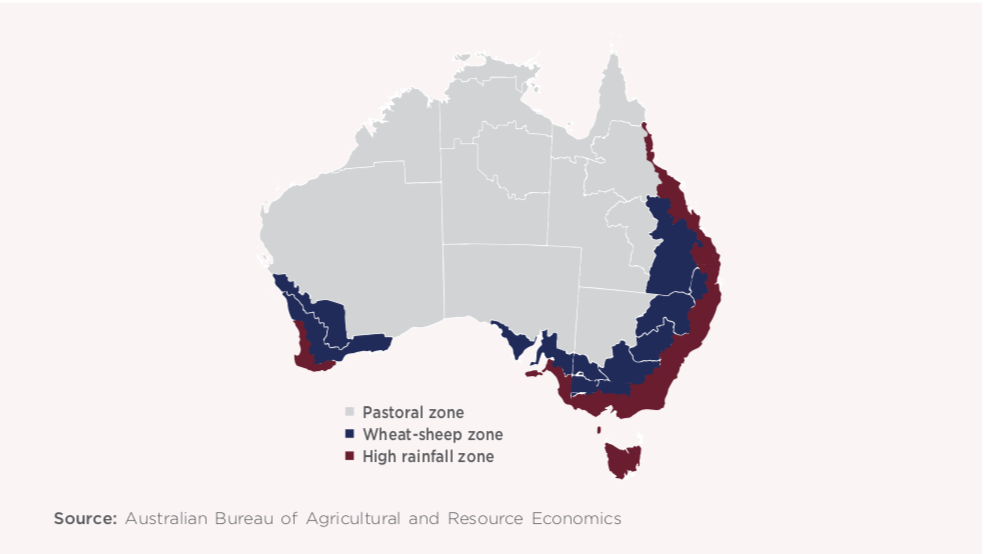

Australia has diverse climatic conditions that are conducive to the cultivation of a wide array of agricultural products. Australian territory can be classified into three broad zones, viz., pastoral, wheat-sheep and high rainfall zones.

The western parts of Western Australia, eastern parts of Queensland and New South Wales and southern parts of South Australia are all parts of the wheat-sheep zone, which is suitable for cropping as it is made up of arable land. The pastoral and high rainfall zones are typically used for grazing of animals as they are not as fertile and hence have lower capacity for cropping.

Majority of the farms in Australia are located in Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales.

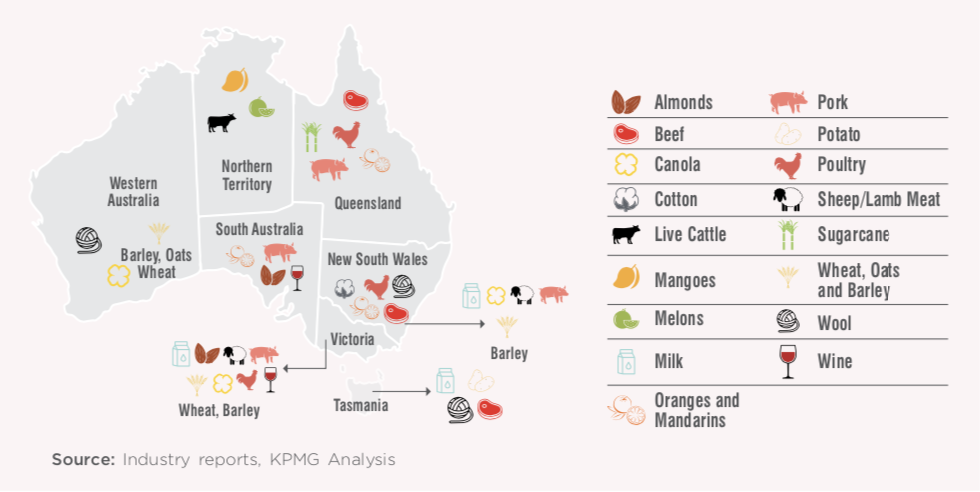

Victoria is the largest producer of almonds and milk in Australia. The state accounts for ~60% of the overall milk production and 73% of almond production, in value terms. It is also the second largest producer of wool (25%)311 as well as sheep & lamb meat (43%).312 Victoria is a significant producer of barley (22%), wheat (14%), canola (14%) and poultry (23%). The state is also known for food processing with companies undertaking over 30% of Australia’s food processing R&D.312

New South Wales is the largest producer of cotton, poultry meat, wool, oranges & mandarins. It is also the second largest producer of beef, milk, canola and sheep/lamb meat. New South Wales constitutes about 63% of overall cotton production in Australia by value.313 The state has the largest poultry flock estimated at ~30 million animals and accounts for 28% of the overall poultry meat production by value. The state is also well-known for its wool production and has a value share of 32% in total wool produced in Australia. The state is also known for its Valencia and Navel oranges and accounts for 43% value share in total production of oranges in Australia.

Queensland is well renowned as a producer of sugarcane, cotton, beef, poultry meat, pig meat and mandarin oranges. Queensland accounts for 95% of sugarcane production in Australia, valued at USD 1.1 billion. The state is home to half of the cotton farms in Australia and accounts for 37% of the country’s production by value. It is the largest producer of beef-constituting 47% of Australia’s beef production by value, second largest producer of poultry meat (24%) and third largest producer of pig meat (23%). The state is also a significant producer of mandarins, accounting for 22% value share of total production.

Western Australia is the largest producer of barley (32%), oats, canola (49%) and wheat (33%) in Australia and the second largest producer of wool (24%). The state also provides raw materials for exports of a large number of processed products including wine, ice-cream, barley malt, noodles and fine leather and is also a globally recognized supplier of lobsters, prawns and pearls.

South Australia is the largest producer of wine in Australia-constituting 42% of total grape crush. Riverland and Barossa valley are the prime wine producing regions in the state. It is also the largest producer of pork (26%), second largest producer of oranges (32%) and a significant producer of almonds (14%). The Waite Research Institute (WRI) that supports research and innovation across Australia’s agriculture, food and wine sectors, is also located in South Australia.

Northern Territory is close to the fast growing and high demand Asian markets and supplies live cattle for both export and domestic markets. The territory has several mango farms and produces tropical horticultural crops such as melons, bananas and Asian vegetables.

Tasmania is known for milk, beef, potatoes and wool. The volcanic soil of Tasmania allows it to produce high quality potatoes. The region is also acclaimed for its superfine wool.

Agricultural exports from Australia

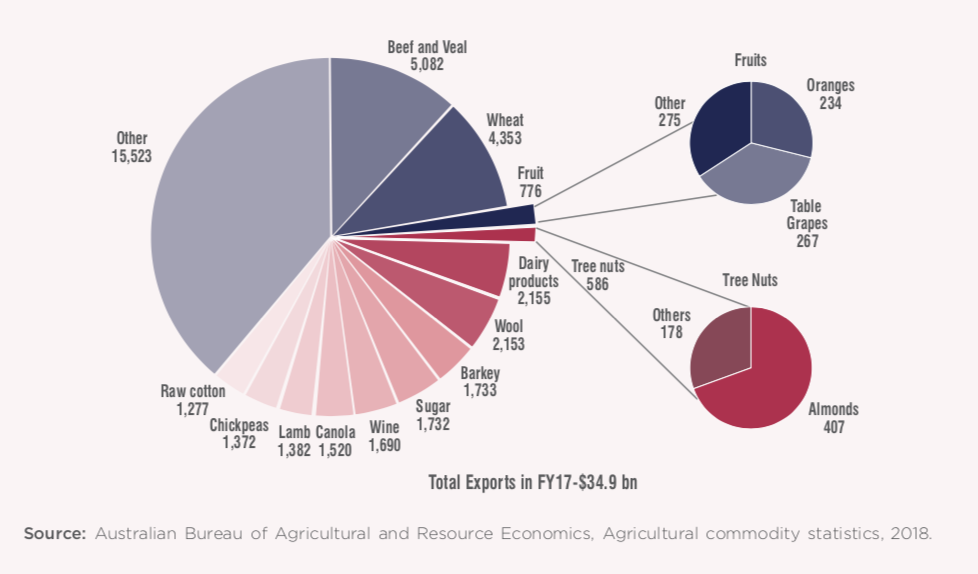

The key commodities exported by Australia are beef and veal, wheat, dairy products, barley, sugar, wine, canola, lamb meat, chickpeas, raw cotton, almonds and oranges. The total agriculture commodity exports from Australia stood at ~AUD 7.3 billion (USD 4.9 billion) in FY17.314 The top destinations for Australia’s agro commodities are China (21%) followed by Japan (10%), the European Union (8%), the US (7%), South Korea (7%) and Indonesia (7%).

Australia is the third largest exporter of beef in the world. The key export markets for Australian beef are Japan (27%), the US (21%) and South Korea (17%).315 Australian beef is considered to be of a superior quality and free from diseases. Australia’s traceability and meat standards gives it a competitive edge in the global market. A few notable beef producing companies from Australia are Stanbroke Pastoral, AA company, Consolidated Pastoral Co. and Kidman holdings.

Wheat exports from Australia were valued at ~AUD 6.4 billion (USD 4.3 billion) constituting 12% of Australia’s total agriculture exports by value in FY17.316 The key export markets of Australian wheat include Indonesia, China, Vietnam, South Korea and Japan. White grained wheat varieties that generate high flour milling yield are produced in Western Australia. Notable companies producing wheat in Australia include family owned companies like Harris family, Stanbroke Pastoral and Sundown Pastoral.

Australia is the world’s largest producer of wool, accounting for one-quarter of the global wool production. It is the leading exporter of fine apparel wool, constituting 90% of the world’s fine apparel wool production.317 China is the largest export market for Australian wool constituting 74% value share followed by the European Union (10%) and India (10%).317

Australia ranks among the top four countries in dairy trade, constituting a 6% share in the world behind New Zealand, EU and US. Of the total production, more than one-third is exported. Asia is the largest market for Australian dairy products, constituting 85% of the total exports. Within Asia, China (27%), Japan (13%), Singapore (9%), Malaysia (7%) and Indonesia (7%) are the key markets. High demand from Asian markets and Australia’s geographic proximity to Asia have led to high concentration of exports to Asia within Australian dairy exports. The total value of Australian dairy exports in FY18 was ~AUD 3.7 billion (USD 2.5 billion). The key products exported include cheese, whole milk powder- including infant powder, skim milk powder and milk. The dairy exports from Australia to China have increased by 164% from FY14 to FY18, with categories like infant powder, skim milk powder and cheese witnessing significant growth.318

Australia is one of the largest barley exporters in the world, constituting 30-40% of the exported malting barley and 20% of the global feed barley.319 China and Japan are the key markets for malt grade barley while the Middle-Eastern countries, mainly Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, are the key markets for feed grade barley.

Australia produces different kinds of red and white wine varieties such as Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot and Sauvignon Blanc. Australia exports ~64% of the wine it produces and is the 5th largest wine exporter in the world. The key export destinations for Australian wines are China (33%), US (18%), UK (14%), Canada (7%) and Hong Kong (5%).320

Australia is the second largest exporter of Canola in the world after Canada. Canola oil can be used as margarines, cooking oil and salad dressings and as a fuel source in farming business operations. Australia’s key export markets for canola include Germany, Belgium, Japan, France and UAE.

Other agricultural products exported from Australia include sheep meat, lamb and mutton, chickpea, cotton, sugar, citrus fruits and almonds. Australia is the world’s largest exporter of sheep meat. Australia is the largest chickpea exporter in the world and its key export destinations are India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. India constitutes a large share (80%) in the Australian chickpea exports. Australia is the fifth largest exporter of cotton with 99% of the raw cotton produced in Australia being exported to countries such as China (55%), India, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia.321 Table grapes and citrus fruits such as, oranges and mandarins are one of the largest fruit exports from Australia. The prime export markets of Australian citrus fruits include China, Hong Kong, Japan, Indonesia and Singapore. Australia is the world’s second largest almond exporter in the world. India is the most important export market for Australian almonds accounting for 40% share in the overall export quantity. Other significant markets for Australian almonds include Vietnam and China. Australia is the second largest exporter of raw sugar in the world and raw sugar constitutes 80% share in the domestic sugar production. The key export destinations for Australian sugar are South Korea, Japan, Indonesia and Malaysia.322

Agriculture in India

Around 70% of India’s population resides in rural areas, where the main occupation is agriculture related.323 India has traditionally been an agrarian economy, with more than 40% of the workforce employed in the agricultural sector.324 A wide array of diverse climatic conditions and soil types have led to India’s agriculture sector being one of the most significant sectors of the economy, contributing 17-18% of India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).325 The Gross Value Added (GVA) by agriculture, forestry and fishing was approximately USD 275 billion in FY18.

India is a leader in the production of food grains, horticulture and livestock. India is the second largest producer of food grains globally with an estimated production of 285 million tonnes in 2018.326 India is the 2nd largest producer of rice and wheat and the largest producer of pulses. It is also a leading producer of cotton (2nd largest), jute (largest) sugarcane (2nd largest), oilseeds and tea.327 India is also a leading producer of fruits (leading in mangoes, bananas, papayas), vegetables (leading in potatoes, onions, cauliflowers) and of fish, poultry and livestock, having the world’s largest cattle herd (buffaloes). It is also the largest producer and consumer of dairy products.

India is one of the top ten exporters of agricultural produce in the world. The two significant contributors to export revenue for Indian agricultural produce are food grains and livestock (and related products). Rice is India’s most valuable export, at approximately USD 8 billion in 2018 especially the famous ‘Basmati’ rice. The Middle East - Saudi Arabia, Iran and UAE – are important markets for India’s rice exports. India also ranks as the second largest exporter of cattle meat (beef), largely exporting to Vietnam, Malaysia and Egypt. India exports around 14 million tons of seafood (worth approximately USD 7 billion) to the USA and South East Asia.328

India is amongst the top five exporters of onions, with exports worth USD 500 million in 2018. India is also the world’s largest processor and exporter (USD 943 million) of cashews in the world. As a pioneer of the cashew industry, India was the first country to introduce kernels to the world market. India is also a notable exporter of coconuts (USD 63 million in 2017) and a key exporter of groundnuts with approximately USD 525 million exported in 2018.

Despite the large agricultural production, India faces significant challenges in this sector. India employs approximately 42% of the population in the agriculture sector. However, this sector contributes only about 17-18% of the GDP in India. This trend reflects the slow adoption of mechanization and the relatively low labour productivity in this sector. While India’s dependency on rainfall for agriculture has reduced significantly over the years, there are still a large number of geographical pockets, which are heavily dependent on rainfall.

There is a limited degree of concentration of land holding in India. Large parcels of lands are held by a small section of wealthy farmers or landlords, while a vast majority of farmers own very little or no land at all. The main constraint to adoption of mechanization in India has been land fragmentation, with a majority of marginal and small landholdings hampering the utilization of agricultural machinery and inadequate access to formal sources of finance for long-term credit.

Additionally, storage facilities in rural areas are inadequate. Indian agriculture faces several challenges such as food wastage, lack of adequate food processing, logistics and preservation and refrigeration facilities. As a result, farmers are forced to sell their produce immediately after the harvest at low market prices. Such distressed sales deprive the farmers of their rightful income.

Key Opportunities

Investing in agriculture technologies in Australia

While India is one of the largest producers of a number of crops such as rice and wheat, it suffers from a relatively low yield (quantity of crop produced per unit of land). For instance, for two of India’s largest produced crops, rice and wheat, India’s yield is far lower than other countries. India has a rice yield rate of 2.4 tonnes per hectare while China and Brazil have yield rates of 4.7 and 3.6, respectively.329 Similarly, India’s yield rate for wheat of 3.15 tonnes per hectare is significantly behind countries such as South Africa and China whose yield rates are 3.4 and 4.9 respectively.330

There are a number of reasons for India’s low levels of productivity, primarily, the fragmentation of farm land holdings leads to a feasibility gap in implementing large scale solutions to the Indian agricultural landscape. The lack of access to modernized technology and processes – for irrigation, automation using machinery, etc. act as a key hindrance for improvement in yields.

In Australia, the use of technology in agriculture has led to an improvement in the efficiency and productivity of animal and plant production systems. Biotechnology, farm management and farm robotics are some of the key areas where Australian agritech has witnessed development and investor interest. Particularly, in biotechnology, the use of genetically modified plants in commercial farming is prevalent for some crops, with extensive use in herbicide-tolerant canola, carnations and cotton. Cotton, one of Australia’s key export commodities, is largely (98%) grown using genetically modified seeds.331 Genetically modified crops however, are heavily regulated and limited in Australia, and apart from the three aforementioned crops, genetic modification is not permitted in most other commercial cropping. Farm management software involves the use of decision support tools to help farmers take decisions that result in improvements in crop production and performance. The use of Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Australian agritech have seen significant innovation and investments from the likes of large corporations like Bosch and Cisco as well as home grown start-ups such as Agrivi, CropLogic, Aerofarms, etc. Incorporating innovative technologies such as driverless tractors, drones to monitor crop health, use of data to drive solutions and Uber-like mobile applications for ferrying fresh produce has revolutionized the agricultural production process.

Large investments in research and development of innovative technologies has brought forth these solutions, leading to high growth in this sector. Specifically, the Government has funded rural R&D corporations to focus on agritech research activities. CSIRO initiatives, such as using Delta Carbon Technology to identify water-efficient plants, have brought about this change. Australian technologies, that drive productivity improvements despite challenging weather conditions, can be leveraged by India.

Possible areas of collaboration with Australia include exchange of germplasm; quality planting material for almonds, grapes, oranges and vegetables for healthy production; capacity building of personnel through knowledge-exchange training and visits; transfer of technology for application in the Indian context in farm management and Artificial Intelligence (AI); post- harvest management specially for cold storage of perishable horticulture produce. In addition to this, possibilities may also be explored for use of Australian solar energized greenhouse technology for North Eastern parts of India.

Collaborations between Australia and India can occur at multiple levels across stakeholder organizations to facilitate the transfer of knowledge and technology for application in the Indian context. This could be in the form of the two Governments driving programs for nodal institutions that oversee the development of the agriculture sectors, to share knowledge on processes as well as to administer the use of new technology in agriculture. It could also take the form of private institutions from India collaborating with other private bodies across the borders or directly with the Australian Government to customize solutions that could be implemented for India’s agriculture.

Indian HNIs, private corporations and the Government can invest in agri-technology and expertise in Australia. Inventions arising from Australian agriculture include the combine header harvester and stump-jump plough and drought and disease-resistant wheat. Australian farmers are also rapidly adopting practices that are highly mechanized to remain price competitive.332

In addition, investment by Indian companies in Australia could also result in research partnerships between Indian companies and CSIRO and other research bodies in Australia, which could benefit both countries. For example, Waite Research Institute (WRI) at the University of Adelaide was established to drive research and build capacity for Australia’s agriculture including research on soil, food and wine sectors. WRI aims to contribute solutions to the emerging challenges of global food security and agricultural sustainability. Researchers at WRI use genomics to understand genetics as well as to produce drought and disease resistant and high-quality varieties of wheat, barley, etc. India could collaborate with such institutes for research.

Another route for investment by Indian companies could be the acquisition of specific agriculture-tech companies/start-ups in Australia. Access to capital as well as resource augmentation is necessary for agri-start-ups to thrive. A report released by KPMG Australia compared six international AgTech players on specified parameters. While Australia scored higher than India on parameters such as capacity to innovate and university- led collaborations, India ranked higher on monetary parameters. Indian companies can thus invest/ acquire Australian agri-tech companies and utilize the technologies that focus on solutions for problems relevant to the Indian context. For example, in 2017, Jain Irrigation Systems Limited, India’s largest micro-irrigation firm, acquired the technology and the core team of Australian agri-tech firm Observant Pty Ltd that is well known for its in-field hardware and cloud-based applications for precision farm water management.333

Source: Australian trade commission partners with Yes Bank to offer Australian agribusiness and food expertise for India, 2013, The Times of India

Source: ITC buys Technico’s India seed potato unit for Rs121 crore, 2016, Live Mint

Australia and India can develop and fund a collaborative agri-food research program focused on tropical conditions farming and agriculture, greenhouse technology and fish farming. The joint R&D programs could increase projects, which are designed to improve food production and logistics practices. Currently, Australia’s Western Sydney University has entered into a partnership with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and thirteen state agricultural universities as a part of a new initiative designed to combat global food security issues presented by climate change.334

Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) has the capability to establish agricultural universities.India has additionally established the Afghanistan National Agriculture Science and Technology (ANASTU) in Afghanistan and the Advanced Center for Agricultural Research and Education (ACARE) in Myanmar.

India currently has three335 Central Agricultural Universities (CAUs) and 64 State Agricultural Universities (SAUs).336 While the institutes in India have contributed towards agriculture research in the country, they require institutional support, better infrastructure and faculty development to be able to achieve international excellence. There is also a requirement for greater focus on innovation-based research in India as well as deeper collaboration with agri- universities and students from other countries. Agricultural education in Australia is highly developed with several universities such as the Australian National University, University of Melbourne, University of Sydney and University of Western Australia, etc. are offering specialized research based agricultural courses. Some of these programs are ranked amongst the top 50 in the world.337

For example, in 2012 a 6-year research agreement was signed between Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC) (representing the Indian Government) and Queensland University of Technology for development and tech-transfer of a bio-fortified and disease-resistant banana variety. This project involved Indian institutes such as National Research Centre for Banana, National Agri-Food Biotechnology Institute, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Centre for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology and Indian Institute of Horticultural Research.338

India can also collaborate with Australia to set up a leading-edge agri-university in India, based on Australian institutes’ world class infrastructure, specialized curriculum and extensive research-based programs as well as work towards upgrading the existing universities in India.

Source: Agtech in Australia: Driving IOT connectivity for farming,

Opportunity for adoption of best practices in dairy processing

India is the largest milk producing country in the world. India produced 156 million tons of milk in 2015-16.339 A large portion of Indian dairy is domestically consumed, leaving very little quantity for export. Demand for dairy products in India is likely to grow significantly over the next few years, driven by growth in population, higher remuneration levels and an increased interest in nutrition. Consumption of processed and packaged dairy products is increasing in urban areas.

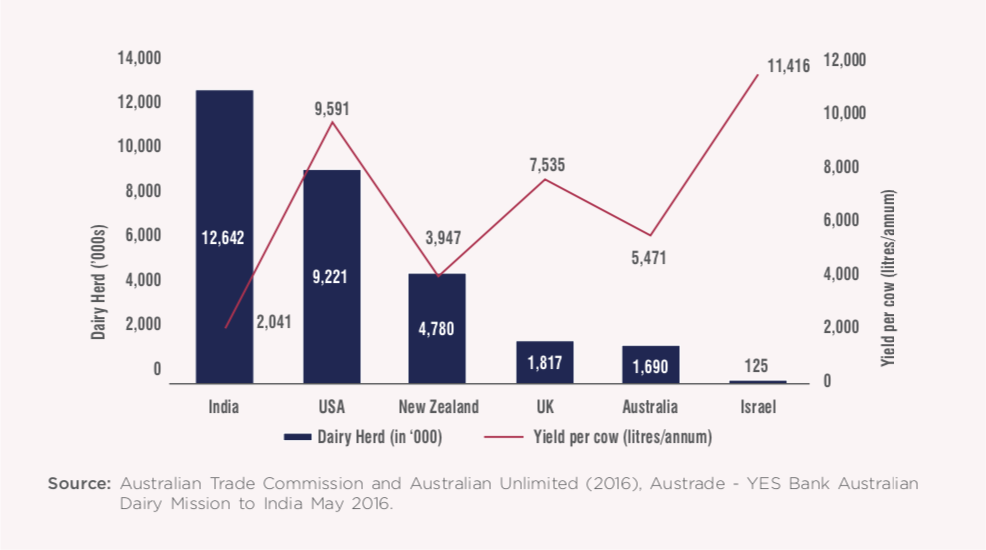

In India, although the dairy sector has developed significantly, with a large stock of dairy herd, the yield per cow is still low. This is primarily due to a number of reasons including genetic deficiencies as well as farming techniques. India has historically focused on cross breeding, which has not improved the indigenous breeds significantly. Furthermore, the limited size of individual herds and the absence of technically skilled labour has led to limited focus on progeny testing and other such methods. Apart from this, there is lack of modernization in farming techniques and animal care, which results in poor nutrition and feed management, inferior farm management practices and ineffective care for cows.

The dairy industry is one of Australia’s most important agricultural industries. The participants in the Australian dairy sector range from farmer owned co-operatives through listed, private and multinational dairy and food specialists. Globally, Australian firms and research centers also use their expertise to provide technology, equipment, services, skills and systems to farmers to improve production in different climates and settings.340 Australia has made significant advancements in its dairy sector on the basis of technological innovations such as milking shed technologies, calving patterns and feeding systems.

Milk shed technologies have increased efficiency of farm operations, through automation of different processes for the milking of cattle, such as cup removal, drafting, cleaning, etc. The use of these technologies has resulted in farmers reaping the benefits of higher productivity, while reducing their labour costs significantly. Owners of cattle herd employ different calving patterns (seasonal, year-round, etc.) in order to maximize their profitability amidst changing climatic conditions, supply of feed materials, etc. In the Australian context, states such as Tasmania, which have had a rather even mix of calving patterns, have experienced higher levels of productivity. Dairy farming in Australia has witnessed a widespread implementation of supplementary feeding, though it is largely pasture based grazing. Regions, which face relatively inconsistent rainfall, have a higher usage of conserved fodder.

Indian HNIs, private corporations and the Government can invest in dairy-technologies and know-how in Australia. Dairy provides several opportunities for an Indo-Australian partnership that can benefit both countries. There is limited exposure to Australian dairy expertise in India. Stakeholders in the Indian dairy sector have more knowledge about the dairy sector in North America, Western Europe (the Netherlands, Germany) and Israel. Investment in Australian technology can improve not only the quality but also the productivity and consequently, the quantity of milk produced in the country. This would also enable expertise in production of processed milk products that can compete with international demand. Technical collaborations in terms of joint ventures/partnerships between large dairy companies in Australia and Indian businesses can become viable business propositions as they combine Australian expertise with Indian cost structures. The technology and know- how of Australian dairy processing can be imported to India and the products manufactured can be sold under an Australian brand name.

Source: Austrade

Educational collaborations and dialogue between both the countries could be increased to facilitate knowledge transfer and spread awareness regarding the latest developments in the dairy industry in both the countries. In the past, such dialogues have helped in strengthening the dairy industries’ relationship between the countries. In 2015, an Australian delegation visited the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in Anand district and Dudhsagar dairy in Mehsana district to pave the way for future collaborations in the Indian dairy industry. Greater visits can be organized to enable Australian companies to understand the requirements of Indian dairy companies.

Opportunities for Australian investments in the Dairy Sector in India

India is one of the world’s largest milk producers, and since milk is a perishable product, it needs to be processed quickly to produce value added products to prevent wastage. Liquid milk has long been the focus of Indian dairy producers. At present, value added products in the Indian dairy industry are largely available in the form of yogurt, cheese and ice cream. Other enhanced products are available but restricted to highly urbanized pockets in the country. Foreign investors in the Indian dairy have either set up independent units or have partnered with local players. Significant investors in the Indian dairy industry include Lactalis (France), Schreiber (USA), Danone (France), Arla (Denmark) and recently New Zealand’s Fonterra via a 50-50 Joint Venture with Future Consumer Products. The Indian government has also permitted 100% FDI under the automatic route in the animal husbandry sector.

Australia’s advanced dairy industry and brands can invest in India to provide new processing, cold chain and storage technologies to produce value added products in India.

Investments in Australian agriculture

One of the largest factors driving Australia’s leading position in the global market for agricultural produce is its strategic location. Its proximity to growth markets in Asia, Middle East and Africa, along with its rich and diverse produce has contributed to the growth in agricultural exports. Australia has finalized free trade agreements with 10 countries, which has made it easier to grow agricultural exports to countries such as China, the US, Korea, etc.

Australia has a robust freight network (spanning both sea and land) that ensures efficient internal transportation of goods, coupled with a strong shipping services network for international outbound logistics, thus enabling timely delivery of exported goods. The robust network of rail and port infrastructure in Australia is a key factor which makes the Australian agri sector attractive to investors.

The aforementioned standards of clean, green produce in Australia are a result of stringent Government regulations on biosecurity. Australia is also at the heart of agritech innovations, which ensure a high level of productivity, thus contributing to surplus production that is available for export.

Factors such as proximity and exposure to growing markets such as Asia, infrastructure network and superior agriculture practices resulting in surplus production, etc. makes Australian agriculture sector lucrative for investments. Indian companies can explore the opportunity to invest in the production of prime export commodities and also identify any other niche Australian commodities to cater to the global as well as Indian markets. Australia has built a very strong brand value on the global platform, which can be leveraged. Indian private companies and MSMEs can invest in both large sized and medium/small sized agro-businesses in Australia. Investments in Australian MSMEs can be used to scale existing processes and mechanisms to a global level and utilize their own existing capabilities in packaging, marketing and distribution to service export demand.

There are very few categories in which India has an export surplus for which Australia has a corresponding supply deficit. However, there are opportunities for specific niche agricultural products such as Alphonso and other mangoes, pomegranates, table grapes, tea, varieties of spices, etc. that are unique to India, which can be exported from India to Australia to develop a market there. Some of these commodity exports have already been initiated, albeit on a small scale. There is a need, however, for continued discussions between the two Governments and making Indian agriculture corporates and exporters aware of phytosanitary and other non- trade conditions and requirements so that they can gain market access in these products in Australia.

With a highly mechanized approach to agriculture, suitable climatic conditions, high quality produce and availability of large tracts of land for farming, Indian companies (as well as individuals) have an opportunity to purchase land in Australia, especially in the Northern Territory and New South Wales where products such as mangoes, chickpeas, cotton, etc. can be grown. This can also provide an opportunity for contract farming to Indian companies to cater to the growing demand for agricultural products in India as well as around the world. The appetite for specific products, such as sweet potatoes, is also on the rise in India and these can be cultivated in Australia to meet domestic demand, especially in areas such as Queensland. Furthermore, availability of water and logistics would be a major factor. Australia is the world’s largest wool producer and Indian companies can consider setting up wool farms in Australia for exports to India and the world.

In addition, several Australian well-known wine brands are imported to India and sold in retail markets via distributors. An alternative to this is to adopt Australian wine processing technology and capabilities locally and manufacture such brands within India. Australian investors may be encouraged to set up joint ventures in India for this purpose. This would bring down costs of Australian wines in India to a great extent and thus make them more accessible to the Indian consumer and would also result in significant quality upgrades for the Indian wine industry.

Supply chain/Logistics enhancement- Getting access to Australian expertise in warehousing

Warehousing is an important part of the overall agricultural system. It is important for stocking both dry as well as perishable produce brought in the market. The majority (66%) of the storage capacity in India is controlled by Government entities - Food Corporation of India, Central Warehousing Corporation and state agencies – while the remaining share (34%) is controlled by other players such as private entrepreneurs, cooperative societies and farmers. Currently, a large part of the rural markets in India do not have integrated warehousing and cold storage facilities, due to which significant amount of produce gets wasted, especially in case of the perishable produce, leading to significant losses.

The farm produce is stored in archaic warehouses and godowns, which are not equipped with any storage technology to control the temperature and moisture conditions, leading to damage by pests, insects and water seepage. Inadequate storage capacity and imbalances in inter-state warehousing availability is another key challenge faced by India. India’s food grain losses are estimated to be 25 million tonnes per annum, which translates to a massive Rs. 45,000 crore (USD 6.42 billion) per year. Farmers are hence forced to sell their produce at low prices immediately after harvest, thus leading to sustained levels of low income. Along with these problems, the majority of farmers lack proper marketing channels and mediums to sell his/her produce.

Australia employs innovative storage techniques such as usage of silo bags and silos to meet its storage requirements. Silo bags are tubes, made of triple layered thick laminated plastic, which protects the grains from damage due to atmospheric conditions and spoilage by pests. The silo structures enable bulk preservation of farm produce for a longer duration. They are the most common medium of storage in Australia, constituting 79% of the grain storage facilities.341 Storage using silos/silo bags is gaining popularity in India as a durable and cost-effective solution to storing food grains to avoid the huge losses incurred from the current archaic storage facilities in place. Moreover, the use of silos/ silo bags involves lower land requirement, labour and transportation costs making it a suitable solution to tackle the loss of food grains in the country. Thus, the Indian Government could tie-up with Australian private companies practicing these techniques to expand the coverage of silo use across India. The Indian Government has a plan to expand the capacity of silos in the country to reach an aggressive target of 10 million tonnes through the public-private partnership mode. Private companies like Adani Agri Logistics Ltd have also invested in building silo capacity in the country. Australia has rich expertise in building and maintenance of silos, which can be leveraged by both the Indian Government as well as private players to upgrade storage facilities in India, through joint ventures and collaborations.

Source: Austrade

While silo bags and silos could prove to be useful solutions to India’s storage problems, they may need to be customized to suit Indian farmlands. Indian farms are highly fragmented and hence a community system is essential for silos to become effective storage solutions in India. This will not be possible without adequate Government intervention.

In addition, Australia has several associations such as the Grain Industry Association of Western Australia (GIWA) and the Grain Research and Development Corporation (GRDC). The Grain Industry Association of Western Australia (GIWA) was established in 2008 to represent the interests of the grains industry across the supply chain. GIWA has members from all grain supply chain sectors including grain growers, consultants, processors, storage and handlers as well as the Government. Grain Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) invests in the Grain Storage Extension Project to provide information and training for growers to use best practices for on-farm grain storage. Collaborations between Indian agricultural bodies with associations such as GIWA and GRDC to carry out joint research on specific storage solutions for Indian agriculture will enable India to reduce wastages.

Sector Representative Contribution: Linfox Logistics

Linfox is a logistics and supply chain company established in Australia in 1956. It is the largest privately held supply chain solutions company in the Asia Pacific region, providing end to end supply chain solutions. It operates in 10 countries namely Australia, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Thailand, Laos, New Zealand, India, Malaysia and Vietnam. Linfox offers a wide range of logistics solutions across supply chain, fleet management, warehousing and distribution, logistics IT, transportation, road and rail freight, intermodal logistics, cold chain, bulk haulage, remote logistics etc. Its end use industries include beverages, dairy and fresh foods, FMCG, government & defence, healthcare & pharmaceuticals, industrial, resources and retail.

Linfox began operations in India in 2006. It operates across 16 sites in North, West and South India, serving the FMCG, beverages and industrial companies in India. They hold ~1.9 million square feet of warehousing space in India. They specialize in plant supply chain, warehousing, transport & freight management, technology and last mile delivery solutions for complex logistics requirements of companies.

Leveraging Australia’s brand equity in food products and advanced food processing technology to tap into the global opportunity

In the consumer space, Australia has innovative food recipes and provides cutting edge food processing technology. Australian snacks are available in various markets around the world, with brands such as Kettle Chips. Australia produces a wide variety of popular spreads including honey, jams and the iconic ‘Vegemite’. Australian consumers are increasingly looking out for new and healthier products with fresh combinations and fewer preservatives. Australian companies such as Beerenberg, Buderim Ginger, Yackandandah Jam and Preserving, Chris’ Dips and Spring Gully Foods have been quick to respond to changing consumer tastes by making gourmet jams and spreads with natural ingredients and innovative packaging.

The Indian market has witnessed a growing preference for new consumer products, favored by prevalent megatrends such as rising incomes and changing tastes of consumers. Food habits of the modern Indian consumer have changed, with a higher propensity to explore different cuisines.

Indian food processing companies can form joint ventures with Australian companies to import Australian technology to India and manufacture food products at a low cost by using Australian recipes to cater to both India and the rest of the world. Similarly, Australian companies should be encouraged to invest in India to leverage the Indian and global markets and to produce at cheaper costs.

Source: Filling up the Indian cookie jar, 2017, Deccan Herald

India can also leverage Australia’s specialized food segregation technologies that separate food qualitatively, i.e. the best quality produce is sent to the market to be sold as raw fruits and vegetables, while the lower quality produce is sent for food processing to make processed food such as jams, jellies, purees, etc. These technologies, if adopted and implemented in India, could significantly increase productivity and reduce food wastage in the country. Australian companies should be encouraged to tie up with Indian partners for providing food processing machinery at lower costs.

Sector Representative Contribution: Heat and Control

Heat and Control is a food processing company headquartered in California and is a noteworthy example of global collaboration in food processing. It is the world’s leading designer and manufacturer of food processing and packaging technology and has operations in the US, Australia, Mexico, China and India. The Australian operations are located in Brisbane and the Indian entity reports to the Australian entity. Heat and Control began its Indian operations in 1997. Heat and Control (South Asia) Pvt. Ltd., is a 100% subsidiary of Heat and Control Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia and has its office and manufacturing facility based in Chennai, India and is responsible for India and the South Asian countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka etc. The company has established a large manufacturing facility in Chennai. The facility is equipped with the latest technology, at par with its global counterparts. The manufacturing facility also includes special customized equipment to manufacture Indian ‘namkeen’ snacks and sweets. This equipment is designed in Australia and the US and is then manufactured and assembled in India. The Chennai office also often receives technical experts from Australia that oversee the application of latest technologies in the factory.

Today, Heat and Control (South Asia) has over 300 employees in various functions such as sales and marketing, production, engineering, planning and service, etc. Initially, Heat and Control only supplied equipment for manufacture of ‘western’ snacks such as potato chips, tortilla chips and nuts, etc. However, the company later realized that the market for Indian ethnic snacks like bhujia, moong dal, etc. was much larger than that of western snacks in India. Heat and Control (South Asia) developed the “Namkeen Line” that produces over 15 varieties of Indian namkeen snacks and most top manufacturers of Indian namkeen snacks use Heat and Control equipment.

Sector Representative Contribution: Riverina Oils and Bio Energy (ROBE)

ROBE is an Australian refined oil producing company. The company crushes 200,000 tonnes of canola seeds per year and refines 85,000 tonnes of canola oil. Their manufacturing facility is located in Wagga Wagga, with an investment more than AUD 100 million which is touted to be one of the largest greenfield food and agri investment in Australia in the last 10 years. The manufacturing unit sourced technology from the Indian company Desmet Ballestra wherein 100% engineering of the plant was carried out by the Indian company. Additionally, the project has been funded by Indian banks such as the State Bank of India and Bank of Baroda as well as some Indian shareholders. Subsequently, the company launched its product (canola oil) in India under the brand name “Wagga Wagga”.

Deep sea fishing and aquaculture

Aquaculture and fisheries are India’s fastest growing sectors. India has a vast coastline, ~7,500 km and an Exclusive Economic Zone of approximately 2.02 million square kilometres. The fisheries sector provides employment to ~14 million people in the country.342 In 2018, India’s shipment of seafood earned USD 7.08 billion344 and during 2017-18, fish production in the country was approximately 12.60 million metric tonnes. India’s fish production constituted around 6.3% of the global fish production342. India exports more than 50 types of fish to around 75 countries. Fish and fish exports contribute 0.91% to the country’s GDP. In 2017, India was the 10th largest exporter in value terms for frozen fish.343 Frozen shrimp and frozen fish are India’s most valuable seafood export items and majority of the products are exported to the US and South East Asia, followed by Europe, Japan, Middle East and China.344

In line with the vast potential of the fisheries sector in India, the Government of India called for a Blue Revolution, in which the Government merged all schemes of the fisheries sector into an umbrella scheme. The new integrated strategy was set out to improve fish production and productivity from aquaculture and deep-sea fishing. While the sector is growing rapidly in the country and has received considerable Government support, it also faces several issues such as wastage and loss of revenue. There is also too much pressure on existing wild fisheries in the country and there is a limited understanding of technology in aquaculture. Further, despite the large numbers in exports of fish and fish products, the deep see fishing sector in the country is largely underdeveloped. Although there is significant potential in this area in India, especially in Tamil Nadu and the Andaman and Nicobar belt, the knowledge about the commercial potential of deep- sea fishing beyond the Bay of Bengal area is limited.345

As per the decision taken by the Island Development Agency, Government of India, in 2018, the Union Territory Administration decided to promote tuna fishing for the development of fisheries sector in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands have a coastline of 1,912 kilometers with a 30% share of the Indian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The fishery potential of the islands is estimated at 148,000 MT per annum which includes 64,500 MT of tuna fishery resources. However, in 2017 only 2500 MT and currently only 3500 MT of tuna have been exploited from this belt. There is thus significant potential in this area. The Andaman and Nicobar administration has proposed an integrated INR 101.8 crore (USD 14.5 million) fisheries development project for harvesting of Tuna and other fish, along with setting up adequate infrastructure facilities such as EIC Labs, online catch and collection analysis projects, transshipment port facilities etc.

Australia has a reputation as a reliable and high-quality supplier of high unit value and fishery products such as rock lobsters, tuna, etc. In recent years, with increase in consumption of sea food around the world, wild catch fisheries have reached their full capacity. Aquaculture is thus a sector that has gained attention to meet the local and global demand for seafood. Australian enterprises in the sector have continuously adopted innovative techniques and sophisticated technology to increase productivity in the sector. The sector generates ~AUD 2.4 billion (~USD 1.6 billion) annually in Australia and employs approximately 10,600 people. The specific items produced in Australia are salmonids, rock lobsters, prawns, tuna and abalone. Australia’s chief export markets are Hong Kong, Vietnam, Japan, China and the US.346

Accordingly, in line with the Indian Government’s Blue Revolution initiatives, India can seek Australia’s assistance in aquaculture and deep- sea fishing in areas such as barramundi fingerlings and hatchery setup processes, pearl oyster harvesting, bio-algae–based aquaculture waste water treatment, high-performing shrimp feed and deep- sea fishing vessel design.347

With a shift in the fishing industry from traditional practices to scientific and technical developments, there is also a dire need for up-skilling personnel in this sector in India. In Australia, the Seafood Industry Training Package (SITP) forms the basis for vocational education and training for the seafood industry. SITP covers all commercial aspects of fishing including harvesting, farming, culturing, storing, processing and selling. Indian Institutes such as the ICAR and State agricultural and fisheries universities can enter into MoUs with such Australian institutes to build a fisheries training program specific to India’s fisheries sector.

Ready to eat products

In recent years, there has been a paradigm shift in the consumption and buying pattern of the Indian consumer. Rapid urbanization, characterized by busy lifestyles, increasing purchasing power and paucity of time have made the Ready to Eat (RTE) and Ready to Cook (RTC) food segment extremely popular amongst urban Indians. During the period 2011-2016, the RTE market in India grew at a CAGR of 14.8%.348 The RTE and RTC segment has also gained popularity due to a large number of Indian tourists and students abroad. As many as 4.7 million Indians travelled abroad in 2017348 and the number of Indian students abroad is also growing. Further, with a growing Indian diaspora abroad, the demand for Indian RTE products has been growing overseas. Consumers around the world are also increasingly becoming conscious about health implications of food and the demand for organic products from India is on the rise due to consumers’ increased preference for products without the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The past decade has seen the emergence of several players in the organic products sector that could also export products to Australia and other global markets. India has a large market in this segment and the country exported organic products worth USD 515 million in financial year 2017-18. The US, European Union member countries and Canada were the biggest buyers of organic products from India. Countries such as Israel, Vietnam and Mexico have also shown interest in Indian organic products.349 In addition to RTE and organic products, other products such as Indian pickles, savouries and snacks have also gained popularity. Indian companies such as Haldiram’s are already offering a wide range of products to customers in that segment. This provides Indian players in this segment with significant opportunities to offer a wide range of products, ranging from healthy organic products to processed and convenient food that caters not just to the Indian diaspora, but also the broader consumer segment in Australia. However, physical quality parameters and packaging norms must be revamped for the Australian market. There is also a need to set up efficient distribution channels.

Sector Representative Contribution: MTR Foods

Indian companies in the Ready to Eat (RTE) foods market have established a large presence in global markets. MTR represents one such global success story. MTR has been exporting its products since the 1980s to over 40 countries and across five subcontinents, with the US and Australia as its largest markets. Australia is an important segment for MTR and the company generates ~10% of its total revenue from Australia. MTR operates in Australia through retail stores such as Coles, Woolworths, etc. It offers a wide variety of food selection ranging from mainstream food products to ethnic Indian food snacks. MTR not only caters to the Indian population in Australia but also towards the large consumer base pivoting towards vegetarianism.

Biofuels

Biofuels are fuels extracted from biomass such as organic wastes and plants. Conventional biofuels include sugar and starch- based ethanol, oil crop- based biodiesel and straight vegetable oil which are the most common commercially produced biofuels around the world. Second generation biofuels can be produced from non-food biomass such as municipal solid waste and third generation biofuels are highly advanced and are produced from micro-organisms like algae. In recent years, there has been a gradual shift towards bio-based fuels and chemicals globally. This is directed by a conscious responsibility and a necessity to reduce dependence on depleting non-renewable energy sources.

India’s biofuel market is at a nascent stage. However, alternative energy sources are the way forward to increase energy efficiency and to reduce greenhouse gas effects in the country. Further, given the country’s vast agricultural sector and easy availability of raw material, generation of energy from bioethanol and biogas has a large potential in the country. The biofuel industry in India also provides tremendous opportunities to uplift many less advantaged rural villages. Biofuels also have a potential to generate large savings for the country. For example, Delhi and Gurugram together consume 1,699,000 tons of diesel in a year. Just for an estimated use, if 5% of biodiesel is blended with petroleum diesel, 84,950 tons of diesal can be saved per year.350

Accordingly, the demand for bio-fuels has been rising in the country. The biofuel industry in India is expected to touch Rs 50,000 crore (USD 7.14 billion) by 2022.351 The Government implemented the National Policy on Biofuels, first in 2009 and then in 2018. Additionally, on World Biofuel Day, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) launched RUCO – Repurpose Used Cooking Oil, an ecosystem that will enable the collection and conversion of used cooking oil to biodiesel. Under the National Policy on Biofuels 2018, the Government set a target to blend 20% of ethanol with gasoline and 5% blending of biodiesel with diesel by 2030.

The biofuel industry in Australia has a large potential. Australia’s specialization in agriculture makes the country predisposed to raw materials for biofuels. According to a study by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Australia’s biofuel industry can add more than AUD 1 billion (USD 0.67 billion) in revenue to the Australian economy. While the industry has some marquee players, the country lags behind other economies such as USA and Brazil. Ethanol and biodiesel are the two main biofuels produced in Australia and ethanol-based petroleum accounted for merely 1.1% of Australia’s total petrol sales in 2015-16.352

The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) has forecasted that the global demand for biofuels will triple by 2050 to reach USD 1.13 trillion by 2022 and most of this demand is expected to be fulfilled through ethanol.352 Accordingly, India and Australia can jointly collaborate, first at a policy and Government level and then at a private organization level, to increase research, not just on first and second generation biofuels but also on advanced third generation biofuel technologies.

Encouraging Australian companies to invest in India’s Mega Food Parks (MFPs)

Since 2008, the Ministry of Food Processing Industries in India has sanctioned around 40 Mega Food Parks to harness potential opportunities and ensure efficiencies in India’s food processing industry. The MFPs are set up over a space of 50 acres, with an aim to provide linkages among farmers, food processors and retailers to ensure waste reduction and enhancement of farmers’ income. These MFPs have been sanctioned across several states including Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Bihar, Tripura, Telegana, Mizoram, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Odisha, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, Karnataka, Manipur, Nagaland, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Kerala.353 As of 2018, 18 of the 40 MFPs were operational.353

Financial assistance up to Rs. 50 crore (USD 7.14 million) is provided by the Government for setting up infrastructure facilities such as cold storage, warehousing, sorting, grading, pulping and packaging units, etc.354 These MFPs are expected to contribute generously to the Indian economy. Each MFP project would have around 25-30 food processing units with a collective investment of around Rs 250 crore (USD 35.7 million). This is expected to lead to an annual turnover of about Rs 450-500 crore (USD 64-70 million) and directly/indirectly employ ~5,000 persons. The Ministry also expects that each food park, on being fully operational, will benefit about 25,000 farmers.353

India has been encouraging FDI in food processing by liberalizing FDI norms and allowing 100 % FDI in manufacturing of food products. In addition, 100 % FDI is also permitted in trading (including e-commerce) of food products manufactured and produced in India.355

Australia can invest in various stages of India’s food processing value chain via these MFPs. This will also provide the means to Australian food processing companies to enter India’s domestic food industry market. Investments by Australian companies in Indian MFPs will not only benefit Australian investors but will also provide significant technological upgrades and know-how for India’s cold storage and food processing industries. In addition, this would also provide Indian companies access to Australian companies with technologies related to food waste management and waste segregation.

Opportunities for Australian investment in India in the Agriculture sector

At present, 100% foreign direct investment (FDI) is allowed via the automatic route into India for the following agricultural activities:

- Floriculture, horticulture, apiculture and cultivation of vegetables and mushrooms under controlled conditions

- Development and production of seeds and planting material

- Animal husbandry (including breeding of dogs), fish farming, aquaculture, under controlled conditions

- Services related to agriculture and its allied sectors

Other than these activities, foreign investment of up to 100% under the government route is permitted in the tea sector, including tea plantations. Further, 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is allowed under automatic route in storage and warehousing including warehousing of agriculture products with refrigeration (cold storage).

Australian companies can therefore explore investment opportunities in India’s agriculture.

Collaboration with Australia to address specific challenges faced by Indian exporters to Australia

Sanitary and phytosanitary measures are quarantine and biosecurity regulations that are governed by the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS).356 The SPS agreement provides its member countries with a set of safety measures, which are to be applied to protect human, animal and plant life from health risks arising from contaminants and toxins in food and the spread of diseases and pests. The Australian Government’s Department of Agriculture is responsible for administrating Australia’s SPS measures.

India is one of the largest producers of a vast number of agricultural commodities. Efficient quality control and food safety are vital for improving India’s export potential. However, SPS measures also have the potential to create barriers for exports, especially for developing countries. There have been instances in the past when Indian exports of spices and marine products were detained in the importing country.357 While there has been some breakthrough in India’s exports of grapes and mangoes to Australia, the volumes for these commodities have the potential to increase in the future. India requested market access in the year 2007 for many vegetables (cucumber, okra, green peas, onion, tomato, potato and gherkin) and fruits (pomegranates, papaya, pineapple, custard apple, banana, guava and orange) which is yet to be allowed. India’s export of prawns, egg products and brown basmati rice to Australia have also faced technical issues. In 2013, the European Commission had funded the EU-India Capacity Building Initiative for Trade and Development project to address trade related issues faced by India.358 Australia and India can collaborate in a similar manner. Australian Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) regulations for import of all agricultural commodities are available at https://bicon.agriculture.gov.au/Bicon. The aforementioned standards are a result of stringent government regulations on bio- security. The aforementioned standards of clean, green produce in Australia are a result of stringent Government regulations on biosecurity. Such matters can be further discussed in Annual bilateral meetings that are regularly held between officers of National Plant Protection Organization (NPPO) Australia and NPPO India. In addition, regular meetings are also held with the Counsellors of Australian High Commission and officers of Department of Agriculture, Cooperation & Family Welfare (DAC&FW) and the Indian Embassy in Australia and officers of NPPO Australia, where such issues can be discussed. Australia can also share the SPS issues for import of livestock and livestock products from India into Australia. Such a collaboration will help India address specific SPS related issues faced in Australia, while also raising the quality of India’s exports. This collaboration can help India with market access for fruits, vegetables and marine products in Australia.

Recommendations

- In line with the Indian Government’s ambition to increase productivity of agriculture, India should seek Australia’s expertise and experience to set up a specialized agri-university in India.

- Australia and India should develop a collaborative agri-food research program focused on farming in tropical conditions, greenhouse technology and fish farming. This program should also focus on improving agricultural productivity and logistics practices.

- Indian government should encourage Australian logistics companies to invest into the Indian agri-logistics space.

- Australian confectionery and food processing companies should be encouraged to invest into the Indian market to set-up a low-cost manufacturing base to supply these products to the local and international markets.

- Indian government should encourage Australian companies to invest in India’s Mega Food parks, as well as processing, cold chain and storage technologies in the dairy sector.

- India and Australia should collaborate to help overcome phytosanitary and technical parameters for augmenting exports of Indian fruits and vegetables to Australia.

307 Australian Bureau of Statistics

308 Australia Benchmark Report 2019, Austrade

309 ABARES insights, 2018, Department of Agriculture and Water Resource

310 National Farmers’ Federation, Food, Fibre & Forestry Facts - A summary of Australia’s Agriculture sector, 2017

311 Why Victoria is the food state of Australia, Global Victoria website, September 2018

312 “Horticulture, Invest in Victorian agriculture and food, Agriculture Victoria, August 2018 Australian Dairy Industry, Dairy Australia”

313 Australia Bureau of Statistics, Value of agricultural commodities produced, no. 75030.

314 Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Agricultural Commodity Statistics, 2018.

315 Agricultural commodities 2018, Government of Australia

316 Agriculture commodity statistics, 2018

317 Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Wool

318 Australian Dairy Industry In Focus 2018 by Dairy Australia

319 Australian Exports Grain Innovation Centre (AEGIC), Australian Barley – Quality, safety and reliability

320 Australian wine sector 2017 at a glance by Wine Australia

321 Food, fibre & forestry facts by National Farmers’ federation

322 Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Sugar

323 70% Indians live in rural areas: Census, The Business Standard

324 Employment in Agriculture Data Set, World Bank

325 Contribution of various sectors to GDP, PIB, Ministry of Finance

326 India’s foodgrain production touched new high in 2017-18, Times of India

327 India at a glance, FAO

328 Indian seafood export touches new high at $7.08 billion, The Economic Times

329 India’s agricultural yield suffers from low productivity, Live Mint

330 Raghavan, 2014, India’s agricultural yield suffers from low productivity hjijijiiijj

331 “Farmers continue to debate the merits of genetically modified crops as Monsanto marks 20 years of GM in Australia, ABC News”

332 Australian Bureau of Statistics, Farming in Australia, No. 1301.0.

333 Jain Acquires Observant Technology – Strengthens Global Commitment to Precision, 2017, Jain Irrigation Systems Ltd.

334 Australian university to help Indian farmers double income, 2018, The Economic Times

335 Central Agircultural Universities, Indian Council of Agricultural Research

336 State Agricultural Universities, Indian Council of Agricultural Research

337 QS world university rankings 2018: agriculture and forestry, 2018, The Guardian

338 India PM Narendra Modi visits ‘Super-Banana’ lab in Australia, 2014, Livemint

339 On World Milk Day, a look at how India became the largest producer and why it continues to be so, 2017, Financial Express

340 Australia Trade Commission and Australia Limited, Dairy Technology and services

341 Austrade

342 About Indian Fisheries, National Fisheries Development Board

343 “Frozen fish export from India continue to see astounding growth by Center for Advanced Trade Research, 2018, Trade Promotion Council of India”

344 India’s seafood exports cross 7 billion, 2018, The Times of India

345 India not Tapping Deep Sea Fisheries Resources, 2015, The Fish Site

346 Aquaculture and Fisheries, Austrade 2018

347 Catching deep sea fishing and aquaculture opportunities in India, 2017, Australian Trade and Investment Commission

348 High growth segments of the delicious Indian food and beverage industry, 2017, Forbes India

349 Global demand for Indian Organic food products on constant increase, 2018, The Economic Times

350 Biodiesel: The Future Fuel of Automobiles in India – Analysis, 2019, News 18

351 By 2022, biofuel ‘will become a `50,000-crore business’, 2016, The Hindu Business Line

352 Biofuel the forgotten renewable energy, report says, 2018, The Sydney Morning Herald

353 Fourteen mega food parks to become operational this year, 2018, Economic Times

354 17 New Mega Food Parks Sanctioned, 2015, PIB

355 India pitches for FDI in food processing industry, 2017, The Hindu

356 Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures, WHO

357 WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and the Indian Experience; Kaul, Rohit;

358 SPS Barriers to India’s Agriculture Export - Learning from the EU Experiences in SPS and Food Safety Standards

Next topic: